energy production: October 2010 Archives

by Jon Bosak

As our regular readers know, we here at TCLocal are engaged in a long-term effort to help develop local responses to energy descent—the condition of decreasingly available energy. The near-term manifestation of energy descent is high liquid fuel prices caused by a leveling and decline in global oil production, and it has been part of our job over the five years since we started TCLocal to keep an eye on the liquid fuel outlook and periodically advise the residents of Tompkins County (in particular, local policy makers) on what we’re finding.

In September, five of us TCLocal contributors had the honor of presenting a panel discussion on “Local Responses to Energy Descent” at the monthly meeting of Back to Democracy in Trumansburg. The audience heard from Katie Quinn-Jacobs on Preparedness; Karl North on Food Production; Bethany Schroeder on Health Care; and Tom Shelley on Energy. Articles by all of these authors can be found elsewhere on the TCLocal.org web site (see the list at the end of this article). It was my job to introduce these responses to energy descent with a quick summary of the outlook for liquid fuels. A version of that introductory presentation serves as our TCLocal article for the months of September and October.

The overview that follows was based on a fresh analysis of the current situation conducted over the summer by a team consisting of myself, Bethany Schroeder, Karl North, and Tom Shelley. Not every detail will be agreed upon by every TCLocal contributor or even by every member of the research team, but it does represent in a general way a shared view of the outlook for liquid fuels over the next decade. Illustrations drawn from the Web are credited where the source is known and are reproduced here under the Fair Use provisions of copyright law.

The Lesson of Deepwater Horizon

Predicting the price of oil is an extraordinarily difficult task even for petroleum experts, which we are not, and the effect of the economic downturn on the oil business has made reliable forecasting almost impossible for the last couple of years. But this summer, one thing, at least, became very clear: the easy oil is gone. That’s not a future development; it’s already here.

U.S. Coast Guard

No one pursues a course as risky, dangerous, and expensive as drilling four miles down into the Gulf of Mexico unless all the easier stuff is no longer available. It doesn’t take a degree in petroleum engineering to see this.

It is enlightening to understand some basic facts about oil extraction, though, so if you’d like to know more about that, click here. You’ll be returned back to this place when you’re done.

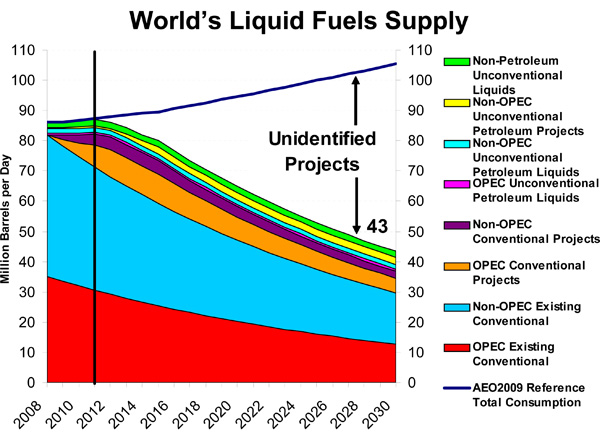

Here’s a recently published official view of the future from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Energy Information Agency (EIA).

The top line in this remarkable graph is world demand for liquid fuels. Over the long term it always increases steadily due to population growth, if nothing else.

The colored areas show the global sources of liquid fuels, taking into account all currently known projects. As the graph makes clear, existing sources of conventional oil are already in steep decline, and unconventional sources can’t keep up with that decline. The result is a growing gap between supply and demand beginning not long after 2012.

In the petroleum world, this has never happened before. Up until now, there has always been enough liquid fuel to meet demand, because it could be pumped out as fast as people had a use for it. A widening gap between supply and demand will eventually have an upward effect on prices beyond anything seen so far.

The label “Unidentified Projects” in the illustration acknowledges that no one really knows what sources can fill this widening gap between supply and demand. It is certain that no combination of currently foreseeable efforts can make up for the rate of decline in conventional oil production, and any new projects are certain to be much more expensive than those of the past.

Red Herrings and Dead Ends

At this point, most readers will be thinking of their favorite solution to the energy problem. But within the ten-year period that we’re discussing here, there is no solution. No current proposal will avert a near-term future of decreasingly less available liquid fuel.

This conclusion may come as a shock to anyone who’s put their faith in technological fixes. We seem to have so many promising solutions to choose from; you’d think the problem was just getting them implemented. There certainly is a lot we could be doing that we aren’t, but on examination it turns out that the proposed technological solutions to the coming oil crunch are at best wishful thinking and at worst border on the fraudulent.

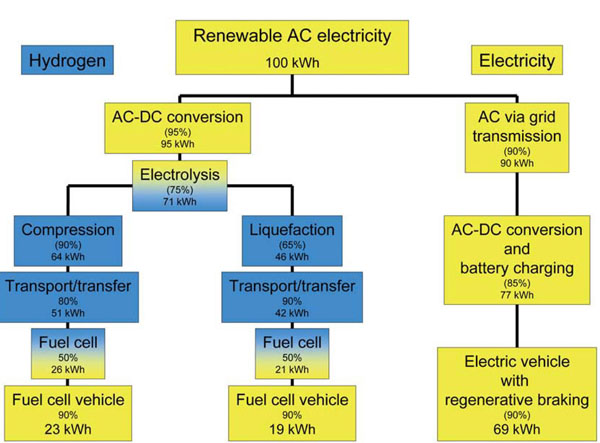

A prime example of this latter category is the idea that we will replace current vehicles with ones fueled by hydrogen. The fact is that hydrogen is not a source of energy, it’s just a way of storing energy, like batteries. And if we had the extra energy to store, we could distribute it much more easily by building out the existing electric grid—and much more efficiently, too. As shown here, the pure electric approach delivers three times the power to the road from a given input of electricity than the hydrogen-based approach.

Bossel, Proceedings of the IEEE

Remember GM’s relentless promotion of hydrogen cars? The last serious publicity the company put into this was in 2006. It’s now obvious that this was all just a PR campaign designed to reassure consumers that GM was working toward a transition away from fossil fuels. That role is now being played by electric cars. This is an improvement, but unfortunately not a solution.

The proposal to solve the liquid fuels problem by transitioning to electricity is one of a large class of putative solutions that make some technical sense but just don’t comprehend the scale of the problem. It’s clear that widespread conversion to electric vehicles will require some kind of addition to our generating capacity, but few people appreciate the size of the change. The fact is that most people have no idea how much energy we’re consuming to move as many vehicles around as we do.

Let’s do a little back-of-the-envelope calculation here. According to the EIA, total U.S. petroleum consumption in 2007 was 20,680,000 barrels per day, and 70 percent of it went to transportation. A barrel of oil represents 1700 kWh of energy. Do the arithmetic and you’ll find that transportation in the U.S. uses about 9.0 billion MWh/year of energy from petroleum. By comparison, according to the EIA, total U.S. electrical output in 2007 was about 4.2 billion MWh. In other words, the amount of energy represented by the fuel we’re using in vehicles is more than twice as much as the total amount of energy represented by the electricity we’re producing each year. Speaking very roughly, therefore, a proposal to replace half of our vehicle fleet with electric versions amounts to a proposal to double the size of our entire electric generating and distribution system, which includes doubling the amount of fuel consumed (chiefly coal). It is safe to assume that we will not see this happening in the next ten years, if ever.

Proposals that rely on solar, wind, or nuclear to provide the missing electricity demonstrate a similar failure to understand the scale of the problem. The following diagram illustrates this point.

Count off the sources by working up from the bottom of the graph and you’ll begin to understand what a tiny proportion of our electrical generating capacity is due to wind, solar, and biomass; their contribution is barely visible. Electricity from nuclear is much greater, of course, but the cost and planning horizon of nuclear projects means that any sizable expansion of nuclear capacity would lie many years in the future. Aside from the inability of these sources provide liquid fuel, no believable expansion scenario envisions any combination of them being able to fill more than a fraction of the energy gap that’s opening up due to the decline of conventional oil.

A third class of solutions would actually solve the liquid fuel problem, but only for a little while, and at an enormous cost in other resources. Hydrofracking for natural gas in our local Marcellus shale is an example of this category of solutions: we get a temporary shot of fossil fuel at the cost of our farms and our drinking water, and at the end of the process we're left back where we started but with permanent damage to our environment.

Another technology in this category is oil from “tar sands” and “oil shales,” production of which uses phenomenally large amounts of water and is even more destructive to the environment than hydrofracking.

Tar sands are also representative of a class of good-looking production technologies that don’t yield significantly more energy than they use but simply substitute one source of energy for another, in this case, massive amounts of natural gas to heat the “tar” (bitumen). Another example of an energy “source” that doesn’t actually deliver significantly more energy than it consumes is liquid fuel from biomass, such as ethanol from corn.

To sum up, then: some of these alternatives—in particular, the development of solar and wind power—really are worth pursuing, but none of the current proposals can change the history of the next decade or so, either because they are not solutions at all or because it is physically impossible to increase production from alternative sources quickly enough to have a meaningful impact in that period of time. The only thing that could change the basic reality would be a massive, all-out effort to replace liquid fuels with substitutes from coal or natural gas.

Large-scale production of liquid fuels from coal has only been accomplished twice in history, once by the Nazi government in Germany and once by the apartheid regime in South Africa; the synthetic fuel is of excellent quality, but the technology is brutally expensive and therefore instituted only as a last resort. And of course large-scale coal-to-liquids would just delay the inflection point without really changing anything, because coal and natural gas are themselves finite resources that are closer to their own peaks than most people realize.

Coal-to-liquids shares one more flaw with most of the other proposed solutions: we’re out of time. A 2005 study commissioned by the U.S. Department of Energy concluded that widespread disruption to our economic system from peak oil could be averted by nothing less than a WW2-level national mobilization effort to implement coal-to-liquids starting at least a decade ahead of the peak—and we don’t have that kind of time left.

Timing the Gap

The inevitability of a coming liquid fuel price crisis caused by failure of oil production to meet increasing demand is much easier to establish than the precise timing of that crisis. But this year several independent studies have arrived from different directions at approximately the same conclusion.

In “The Status of Conventional World Oil Reserves,” published recently in the journal Energy Policy, researchers Owen, Interwildi, and King conducted an in-depth survey of all currently available information regarding oil production and petroleum reserves, with special attention to the reliability of reporting in the OPEC countries. Their conclusion:

Supply and demand is likely to diverge between 2010 and 2015, unless demand falls in parallel with supply constrained induced recession.

Note the “unless”; we’ll return to that shortly.

In the article “Forecasting World Crude Oil Production Using Multicyclic Hubbert Model,” published last April in Energy & Fuels 2010, a team from Kuwait University (Nashawi, Malallah, and Al-Bisharah) performed an in-depth mathematical analysis of the 47 leading oil-producing countries. While based on a methodology completely different from that used by Interwildi et al., their findings are strikingly similar:

World oil reserves are being depleted at an annual rate of 2.1%.... World production is estimated to peak in 2014....

A third independent study is notable for its source: the United States Joint Command (that is, the U.S. military establishment). Their official public assessment of the current situation, published last February in Joint Operating Environment 2010, is short on detail but very clear:

By 2012, surplus oil production capacity could entirely disappear, and as early as 2015, the shortfall in output could reach nearly 10 MBD.

Ten million barrels per day (MBD) is about 12 percent of current global oil production. A shortfall of that magnitude would have an effect on fuel prices that’s difficult to fully imagine.

The mainstream business press has until recently been notably dismissive of such estimates, regardless of the credibility of their sources (how can you dismiss the entire U.S. military?). But in September, Forbes, which bills itself as the “capitalist tool,” broke the wall of denial in an interview with respected oil analyst and oil industry veteran Charles Maxwell (nicknamed “the Dean of Oil Analysts”). Maxwell said:

A bind is clearly coming. We think that the peak in production will actually occur in the period 2015 to 2020. And if I had to pick a particular year, I might use 2017 or 2018. That would suggest that around 2015, we will hit a near-plateau of production around the world, and we will hold it for maybe four or five years. On the other side of that plateau, production will begin slowly moving down. By 2020, we should be headed in a downward direction for oil output in the world each year instead of an upward direction, as we are today.

As might be expected, the estimate in Forbes is the most conservative of the forecasts quoted here, but even it clearly sees a fundamental change in the liquid fuels supply before the end of the decade.

These are just the most recent in a series of warnings by eminently credible sources dating back to 2004. For some earlier quotes, click here.

Now let’s take another look at that first study. It says that supply and demand are likely to diverge between 2010 and 2015, unless demand falls in parallel with supply constrained induced recession. In other words, this forecast, like the rest, is based on the assumption that the economy stays healthy, because (as just happened) an economic downturn reduces the demand for liquid fuels. So we can sum up all four of these recent analyses in one conclusion:

IF the economy stays healthy, THEN supply shortages or very high prices will begin to develop before the end of this decade, probably some time between 2012 and 2015.

In forecasting the timing, therefore, the operative question is, How likely is it that the economy will stay healthy? And the answer is, Not very. This is because fuel prices and the economy have become deeply interdependent. Just as a bad economy causes fuel prices to fall (as we saw in 2008), so high fuel prices cause the economy to fall. An often cited threshold is $85 per barrel, above which the price of fuel has a damaging effect on the economy. Our current economic downturn was about bad credit and a real estate bubble, but some analysts suspect that the first card to be pulled out of the house of cards was the spike in oil prices that briefly drove crude to $145 a barrel.

Instead of the steady decline shown in the EIA graph, we may see a period of boom-and-bust cycles where a rising economy causes a rise in fuel prices followed by an economic downturn and falling fuel prices. If this happens, the point at which global demand permanently exceeds global supply may, contrary to all the estimates quoted above, be pushed clear into the next decade. But this does not affect the basic finding that, as a society, we will soon use much less liquid fuel, for several reasons.

First, from here on out, both sides of the boom-and-bust cycle limit the amount of fuel we will be consuming on average. Either we will be employed but unable to afford the high fuel prices associated with a good economy, or we will have lower fuel prices in an economic downturn but be unable to buy any because we’re unemployed.

Second is the fact that the U.S. imports most of its oil. So for us, the question is not how much oil is being produced globally, but how much of it is available for import. And from this viewpoint, the picture looks very dark indeed. All the big oil exporting countries have internal development needs to meet at the same time that almost all of them are producing less oil every year. The combination of increasing internal consumption and decreasing oil production can very quickly send exports from a given country to zero.

A third factor that guarantees less fuel available to us in the future is China’s quiet acquisition of long-term contracts with major oil producers, which will take a lot of oil out of the open market we’ve been depending on to supply our needs.

Finally, the notion that the global economic cycle will be driven by our national vicissitudes is based on the assumption that the world economy depends on the U.S. economy. That’s been true till now, but the moment the Chinese realize that instead of lending us money to buy their products, they can lend themselves the money to buy their products, we fall out of the picture, and at that point we may well find ourselves with a decreasing ability to pay for fuel that is becoming increasingly expensive, with prices driven upward by an Asian economic expansion that has decided to go on without us.

A Dangerous Situation

The more we consider the dependence of our economy on cheap fuel, the more fragile it appears. Everything about the American economy is based on the assumption that growth is inevitable; indeed, compound interest itself—the bedrock of our financial system—is based on this concept insofar as it represents actual growth and not just inflation. Take that growth away, and the whole thing collapses, as we saw when real estate prices stopped increasing.

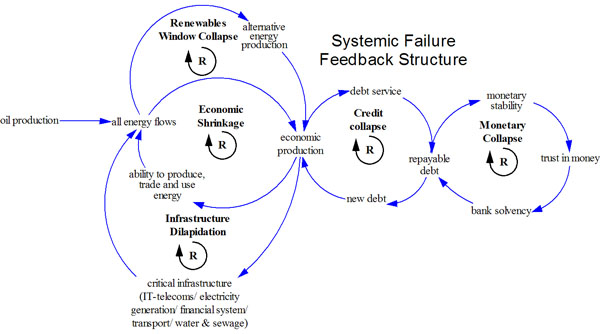

The unprecedented disappearance of spare liquid fuel production capacity makes the system highly vulnerable to interruptions in supply, as diagrammed here by TCLocal contributor Karl North; a problem with oil production (far left) can set in motion a set of feedback loops that brings down the entire economic system. From this perspective, our current situation is actually rather precarious.

While it’s devoutly to be hoped that we can get past the inflection point of oil production with our society more or less intact, no one should underestimate the downside potential of this development. Another recent objective analysis, this one carried out by the German Army (the Bundeswehr), summed up the consequences of declining oil production for their country this way:

Investment will decline and debt service will be challenged, leading to a crash in financial markets, accompanied by a loss of trust in currencies and a break-up of value and supply chains—because trade is no longer possible. This would in turn lead to the collapse of economies, mass unemployment, government defaults and infrastructure breakdowns, ultimately followed by famines and total system collapse.

There is no reason to believe that the potential damage we could be facing here in the U.S. would be any less than in Germany, which is one of the richest and most advanced countries in the world and one that has put far more effort into transitioning to alternative energy than we have.

The Outlook for This Decade

These considerations lead to the conclusion that the watchword for the coming decade is instability. We will probably cycle between economic hardship and high fuel prices for a while, and this cycle will militate against constructive responses. When the economy is bad, we won’t have the money to spend on sensible measures like alternative energy and mass transit, and when it starts to recover, we’ll tell ourselves that the problem was temporary and that we’ll soon be back to business as usual. It’s an old story: when the roof leaks, it’s raining too hard to fix it, and when it stops raining, a fix isn’t needed…until the whole thing comes down on our heads.

As murky as the future appears, however, some things are fairly easy to predict. Here is a list of things that will probably have occurred, or at least be starting to occur, by the end of this decade.

-

Liquid fuels and energy in general will be more expensive. This one’s easy. Even if we could keep expanding oil production (which no one who has looked into it believes), that oil will become increasingly more expensive to extract as we are forced to look farther out into the ocean for it.

-

Less fuel will be available to use. This is another easy call; either fuel will be too expensive, or we won’t be in a position to buy as much as we used to.

-

We will have begun to stay closer to home. This is already happening. Another way to put it is that life will become more local.

-

Supply chains will have begun to contract. This is another direct consequence of rising fuel prices. The distance that goods travel to market became noticeably shorter in just the few months during which we experienced the last price spike. Consequences include a shift back to more local production.

-

Food (as a percentage of income) will be increasingly expensive. Yet another direct consequence of the increasing price of fuel, which is used in enormous quantities both to produce food and to transport it over long distances. Farm land will increase in value, and farm employment will rise as manual labor begins to replace energy provided by liquid fuels.

-

We may begin to see occasional interruptions in some services (electricity, water, sewer, internet, etc.). This one is not as obvious as the preceding, as none of these services are directly impacted by the price of liquid fuels; but huge quantities of liquid fuel are consumed in maintaining all of these service infrastructures, and rising fuel prices will probably result in deferred maintenance and a possible consequent lack of reliability. I don’t think this is likely before the end of the decade, but it’s certainly a possibility, and one that should be planned for.

-

Rationing of fuel and perhaps even food is possible by the end of the decade. Rationing would demonstrate real sensitivity for the social justice aspects of the situation, so I don’t expect to see it happening any time soon, but it’s a possibility.

Some broader developments are simply continuations of current trends that will be accelerated by high fuel prices and their effect on the overall economy.

-

Our standard of living will continue to fall. U.S. household income in real dollars peaked in 1998-1999 and has been declining ever since. There’s no reason to believe that this trend will be reversed.

-

Fewer financial resources will be available to government. This is another development that’s already underway, and it means that most meaningful responses will have to come from individual efforts or self-organized community action.

-

Providing health care for all will be increasingly difficult. Responses include better health education, free clinics, citizen involvement in county public health advisory boards, and the assumption of greater responsibility for maintaining our own health.

-

Military conflict over resources will become increasingly likely. Which is, of course, why the U.S. Joint Command is so interested in our energy outlook!

Final Thoughts

Three observations come out of all this.

The first half of the decade (2010-2015) looks better than the second half (2016-2020). If you have any major projects in mind, this might be a good time to get going. In particular, this would be a good time to make infrastructure improvements, establish a garden, and move closer to work (or arrange to work closer to home).

The developments listed above as possible by 2020 are virtually certain by 2030. The descent doesn’t stop until we’ve achieved a state of equilibrium with a much lower level of resource exploitation. That transition can be easier or harder depending on how we approach it.

A lot of these developments can be prepared for. And that is the purpose of TCLocal: to begin to plan for the future looming on the near horizon. We hope that the foregoing gives the context for our effort and that the articles we’ve published here are helping us begin to confront and plan for the challenges facing us over the coming decade. The following list provides links to all the articles we’ve published so far.

Fruits in a Post-Peak Tompkins County

by Angelika St. Laurent (January 2008)

Roads and Bridges in a Post-peak Tompkins County

by Simon St. Laurent (March 2008)

Water Treatment, Water Power

by Jon Bosak (May 2008)

Post-Peak Land Use Part 1: Ecocities

by Josh Dolan (July 2008)

Post-Peak Land Use Part 2: The Country

by Josh Dolan (July 2008)

Preparedness Basics

by Katie Quinn-Jacobs (September 2008)

Health Care in an Energy-Constrained Environment, Part 1

by Bethany Schroeder (October 2008)

Local and Urban Small Livestock and Poultry

by Angelika St. Laurent (December 2008)

Wasting in the Energy Descent: An Outline for the Future

by Tom Shelley (January 2009)

Food Processing in Tompkins County

by Persephone Doliner (February 2009)

Examining the Potential Local Foodshed of Tompkins County

by Christian Peters (March 2009)

Can New York State Feed Itself?

by Jon Bosak (June 2009)

Visioning County Food Production, Part 1

by Karl North (July 2009)

Visioning County Food Production, Part 2

by Karl North (September 2009)

Burning Transitions: How Planned, Localized, Sustainable Non-food

Biomass Utilization Can Help Ease Energy Descent and Mitigate

Global Climate Change

by Krys Cail (October 2009)

Health Care in an Energy-Constrained Environment, Part 2: Options

for Re-evaluating Care Resources

by Bethany Schroeder (November 2009)

Heating with Biomass in Tompkins County

by Krys Cail and Tony Nekut (January 2010)

Visioning County Food Production, Part 3: Seeing County Food

Production as an Integrated Whole

by Karl North

(February 2010)

Funding and Finagling the Transition to Biomass Heat and

Power

by Krys Cail (April 2010)

Visioning County Food Production, Part 4: Urban

Agriculture

by Karl North (May 2010)

Visioning County Food Production, Part 5: Peri-urban

Agriculture

by Karl North (June 2010)

Visioning County Food Production, Part 6: Rural

Agriculture

by Karl North (July 2010)