Can New York State Feed Itself?

by Jon Bosak, TCLocal Editor

For someone who believes, as I do, that decreasing availability of cheap fossil fuel will eventually make the transportation of food over long distances economically unfeasible, the phrase “local food” acquires a special meaning beyond the usual lifestyle implications. It’s less about maintaining moral purity and more about whether we’re going to have enough to eat. Since I live in the state of New York, the question becomes: could New York feed itself on what it produces?

A couple of years ago, I attempted a back-of-the-envelope sort of calculation to answer this question from a “peak oil” standpoint. To model the worst case, the one in which it takes more energy to extract fossil fuel than the energy we can get out of it, I put the question this way: if New York State produced what it did a hundred years ago, before the arrival of gasoline- and diesel-fueled equipment, could it feed its present population?

The answer, based on New York State agricultural statistics from the 1900 U.S. census, was rather depressing. Despite the fact that New York back then was an agricultural powerhouse — being, for example, far and away the number one state in potato production — its 1900 output of food would barely keep its current population alive.

Carbs weren’t so bad; assuming, in round numbers, a state population of 20 million (a little more than the current estimate), NYS 1900 could annually provide each resident with 87 pounds of corn and wheat and 114 pounds of potatoes. But protein was another story. NYS 1900 could provide each current resident with just 16 pounds of beef and pork, 37 eggs, and half a chicken per year. Dairy production, a historical strength in the state, would provide each person now living here just 39 gallons of milk per year, including an average six pounds of butter and seven pounds of cheese. This is probably enough animal protein to sustain life, but not remotely what we’re used to.

NYS fruit wouldn’t take up much of the slack, either; apples, grapes, peaches, pears, and berries put together would only amount to about 75 pounds per person. New York invented beans as an article of commercial North American agriculture (the first commercial bean crop on record was grown in 1836 in the Town of Yates, in Orleans County), but each person in our current population would only get about four pounds of them a year, plus a little less than a pound of peas. The problem, of course, is that in addition to cutting the fossil fuel input (including all the natural gas we turn into fertilizer), we would be trying to feed almost three times the number of people today that we supported in 1900.

Obviously this calculation was based on some very pessimistic assumptions about available fuel. But it also contained some extremely optimistic assumptions as well — most importantly that we still had substantially more arable land than we actually do now and also that we still had the vastly greater resources of animal power available a hundred years ago.[1] While suggestive, it wasn’t a very precise way of assessing our current resources.

The Cornell studies

Unknown to me, teams at Cornell University under the direction of postdoctoral researcher Christian Peters were engaged in sophisticated studies that would answer a more immediately interesting question — not what would happen if the energy inputs failed, but what the state’s carrying capacity is now, given current rates of production, and what our distribution system would look like if food miles were reduced as far as possible.

The work undertaken so far by Peters et al. has been described in two articles published in the journal Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems. The first piece, from 2006,[2] investigated the influence of diet on the demand for agricultural land and, secondarily, the ability of New York State to reduce environmental impacts by supplying food locally. The second study, from 2008,[3] focused more closely on local food by developing and applying a method for mapping NYS foodsheds. While preliminary, the results of these studies pose serious questions for those who seek to relocalize our diet, and they raise some significant issues for planners attempting to grapple with the contraction of agricultural supply chains due to rising fuel prices. The purpose of this article is to make the key findings of these seminal studies available to a larger audience.

The relatively short list of products actually produced in our climate suggests that the answer to the question of how much of our food needs can be supplied locally depends to some extent on what kinds of foods we plan to eat. The 2006 study approaches this issue by using USDA data to define 42 different nutritionally complete diets supplying 2300 calories a day, calculating the agricultural land requirements for each diet, and then calculating the potential ability of NYS to supply that diet to each resident based on recent estimates of available agricultural land (not land currently in production, but land that could be). Each of the 42 diets is nutritionally complete but contains different proportions of meat and eggs at rates from 0 to 12 ounces per day and different proportions of calories from fat ranging from 20 to 45 percent of total calories. The average U.S. diet contains 5.8 ounces of meat or eggs per day and 41 percent of calories from fat; Figure 1 shows where this average diet falls in the six by seven matrix formed by the two variables.[4] While obviously incomplete, the model does represent the range of common American food consumption patterns from low-fat lacto-vegetarian to high-fat, meat-rich omnivorous.

Figure 1. Matrix of 42 complete diets. (Click for larger image.)

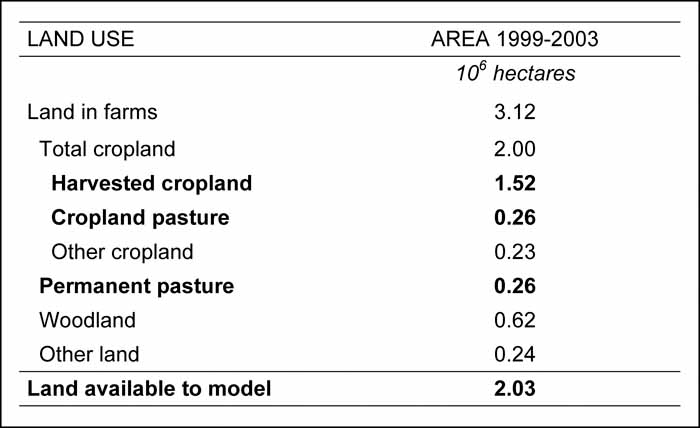

Land requirements for each diet are based on a division of available agricultural land into three categories: harvested cropland, cropland pasture, and permanent pasture.

Figure 2. Available agricultural land in New York

State. (Click for larger image.)

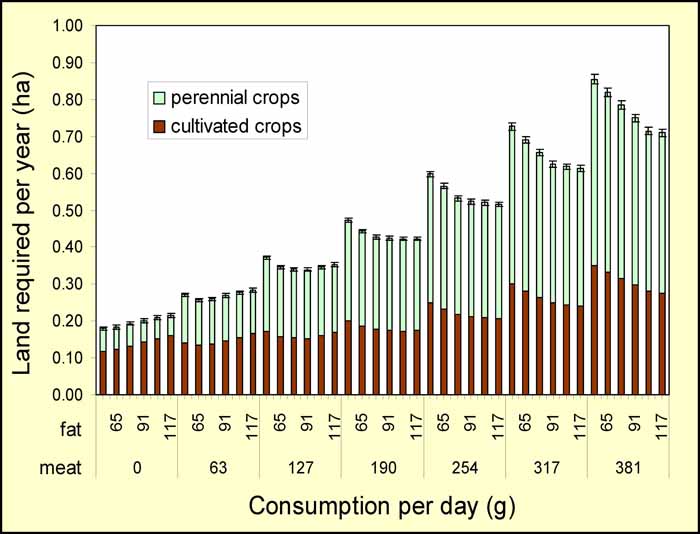

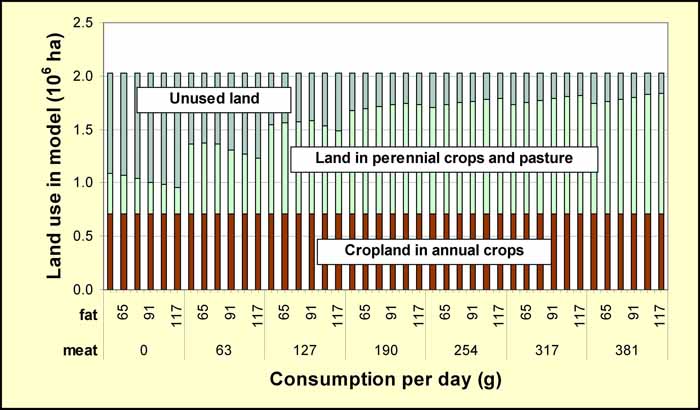

Further methodology, detailed in the study, addresses the interdependencies between perennial crops (grown mainly on grassland) and annual crops (grown mainly on cultivated land), and the calculation of carrying capacity employs a conditional equation that determines which category of land is limiting to food production. Figure 3 shows the results, with the seven levels of meat consumption displayed across the bottom and the six levels of fat consumption grouped within each meat consumption level. For example, someone who ate 190 grams (6.7 ounces) of cooked meat equivalents per day would require somewhere in the neighborhood of 0.45 hectares (about 1 1/8 acres) of combined annual and perennial NYS crops for their sustenance if their entire diet came from within the state.

Figure 3. Land requirements of complete

diets. (Click for larger image.)

Effect of diet on carrying capacity

Not surprisingly, the results show a nearly fivefold difference in the amount of land needed per capita depending on the diet, from 0.18 ha (0.44 ac) for a diet of 0 g meat and 52 g fat to 0.86 ha (2.12 ac) for a diet of 381 g meat and 52 g fat. As most TCLocal.org readers are aware, animal products require much more land per unit of edible energy than grains; in NYS this amounts to 3.3 to 6.3 times as much total land required for the animal products other than beef and a whopping 31 times as much for beef.

On the other hand, as shown in the figure, much of the difference is in the amount of land devoted to perennial crops rather than cultivated crops. If we consider just cultivated land requirements, the clear animal products winner is whole milk (1.2 square meters of cultivated land per 1000 calories). This is just slightly above the figure for grains (1.1 square meters per 1000 calories) and actually below the requirements per 1000 calories for oils (3.2 square meters), pulses (2.2 square meters) and even vegetables (1.7 square meters).

Beef is always presented as the bad boy in discussions of agricultural requirements, but this seems to depend on where you are. The fact is that a lot of the NYS agricultural land base is not suitable for the production of annual crops but is great for forage, which provides most of a ruminant’s nutritional needs. Grassland (I will note) also requires much less in the way of fertilizer and energy inputs and helps to conserve topsoil and nitrogen. Most other foods, including most other animal products, require annual crops, the land for which is more limited in extent and is therefore the limiting factor in the total NYS food supply. Using NYS production figures, the study finds that beef (all cuts) requires 5.3 square meters of cultivated land per 1000 calories, whereas pork (all cuts) requires 7.3 square meters and chicken (all cuts) 9.0. The energy implications of these findings are not brought to the fore in the articles under review here, but clearly the effect on total production and energy requirements of including various kinds of meat in the diet is to some extent location-specific and not as straightforward as it’s often assumed to be.

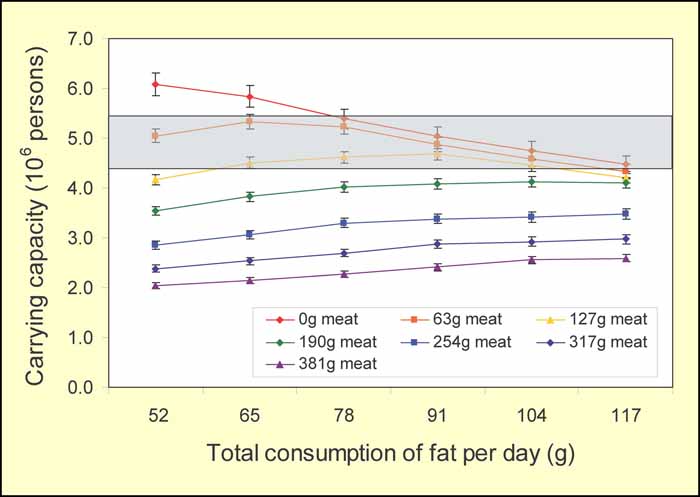

Another nonobvious outcome that can be seen by studying the different fat proportions for each meat consumption level in Figure 3 is that increasing the amount of fat in the diet somewhat reduces the amount of land required. As a result, the difference in carrying capacity due to differences in diet is closer to threefold rather than the fivefold difference suggested by Figure 3. This is summed up in Figure 4, which shows the potential carrying capacity of the NYS agricultural land base for each of the 42 diets. In general, the population supported by NYS decreases with increasing fat in the no meat diet, reaches a peak and then declines in the 63 and 127 g meat diets, and increases with increasing fat in the 190-381 g meat diets. As indicated by the grey shading, some diets with low to modest levels of meat feed equal or greater numbers of people than lacto-vegetarian diets with moderately high levels of fat.

Figure 4. NYS carrying capacity according to

diet. (Click for larger image.)

One possibly unexpected implication of the study is that a vegan diet does not support the maximum number of people, at least not in the state of New York: “[W]e conclude that the inclusion of beef and milk in the diet can increase the number of people fed from the land base relative to a vegan diet, up to the point that land limited to pasture and perennial forages has been fully utilized.” Figure 5 shows what’s meant by this; even the diet with the highest proportion of meat still doesn’t exhaust the land available for forage.

Figure 5. Use of available NYS agricultural land by

diet. (Click for larger image.)

In a passage sure to provoke some of our readers, the authors continue: “[T]he higher populations supported by lower fat, non-vegetarian diets relative to higher fat, [lacto-]vegetarian diets support the claims by animal scientists that the inclusion of animal products in the diet can increase the amount of humanly edible calories available in the food supply. Indeed, more substantial differences may have been observed had a vegan diet been included among the diet scenarios.” The authors hasten to add that this is not an endorsement of the average American diet: “Nonetheless, it is critical to note that the area of overlap observed occurs between 63 g (2 oz) and 127 g (4 oz) of meat, far below the 163 g daily consumption of the average American.”

Beyond these details, Figure 4 also provides the answer to my original question: Can NYS feed itself? The answer is an unequivocal No. Assuming that everyone gets a complete, balanced daily diet that includes 190 g of meat and contains 30 percent fat, the state could potentially feed about 21 percent of its current population. Given a radical change in the average diet, this proportion could, judging from Figure 4, rise to a little over 30 percent, but it’s clear that NYS will always be a net importer of food. Since the cost of transporting food from outside the state is certain to increase dramatically over the next couple of decades, the effect on food prices can readily be imagined. I think this also suggests that economic forces will push back into production some land no longer considered agricultural (golf courses, lawns, etc.).

A subsidiary but still interesting question for people living out here in Tompkins County is whether the situation just described is the same for all parts of the state; after all, a basic (if mostly tacit) assumption of relocalization is that things aren’t going to be the same everywhere. Peters et al. address this question in the second of the two articles reviewed here.

Foodsheds

The 2008 paper takes on the question of what we mean by “local” in an increasingly urban civilization. “To what degree can food be produced locally?,” the study asks. “Moreover, should the meaning of ‘local’ be context specific?” The method is based on a relatively recent reintroduction of the concept of a foodshed, first used by W.P. Hedden in 1929. Peters et al. define a potential local foodshed as “the land that could provide some [specified] portion of a population center’s food needs within the bounds of a relatively circumscribed geographic area,” or more simply, “the area of land that feeds, or could potentially feed, a population.” Foodsheds provide a framework for analyzing the capacity to produce food locally at the scale of an individual city, and a principal goal of the 2008 study is to develop standard methods for this kind of analysis.

The model created in support of this goal employs geographic information systems (GIS) to estimate the spatial distribution of food production capacity relative to the food needs of a given population center and then applies optimization tools “to allocate production potential to meet food needs in the minimum distance possible.” The software implementing the model also produces foodshed maps that aid in visualizing the geographic extent of a food supply.

Assuming a constant basis in the land use data from NYS, it’s apparent that studies of this kind will produce different results depending on the assumptions regarding nutritional requirements and the algorithms built into the foodshed optimization technique.

Since the focus in the second study is on foodsheds rather than dietary variables, it holds those variables constant by using just a single representative complete diet containing 6 ounces daily from meat and eggs and 30 percent of calories from fat. A number of other simplifying assumptions are needed to make it possible to do the spatial modeling; for example, because the concept of a foodshed is tied to population centers, rural NYS residents are assumed to get their food from the nearest center. Also, and crucially, the model seeks to find the minimum total distance food would optimally travel throughout the state rather than optimizing for an individual population center, since the most efficient allocation for the whole state might require that land near one population center be assigned to a more distant population center. Due to matrix size constraints imposed by the spreadsheet software, only 125 of the 132 statistical NYS population centers could be included in the model, resulting in the elimination of the seven smallest (totaling just 0.2 percent of the state’s population).

Even with these simplifications, the optimization model used to calculate foodsheds is quite complex, and I’ll have to refer readers who want more details to the published study itself.

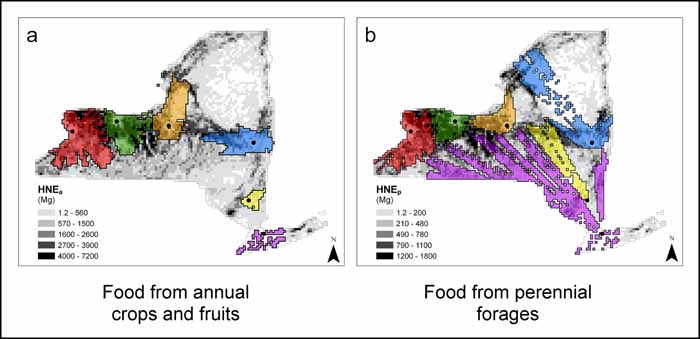

A selection of the output produced from the model for the largest NYS population centers is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Statewide maps of selected

foodsheds. (Click for larger image.)

These maps show foodsheds for food from annual crops and fruits (on the left) and food from perennial forages (on the right) for the six largest consumption zones in New York State: Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse, Albany, Poughkeepsie-Newburgh, and NYC. These six foodsheds, indicated by the different colors, are layered over greyscale shadings showing the capability of different areas of the state to produce food. For example, the completely black pixels in the map on the right show that the area represented by those pixels in the original model (not necessarily scaled the same as the pixels here) is potentially capable of producing 1200 to 1800 metric tons (Mg) of food products annually from perennial crops, chiefly pasture. HNE stands for “human nutritional equivalent,” referring to a complex submethodology for relating per capita nutrional requirements to combinations of farm products.

As can be seen from these maps, the presence of a population center much larger than the rest changes the shape of the other foodsheds. For example, on the perennial forages map, the Syracuse, Albany, and Poughkeepsie-Newburgh foodsheds extend farther to the north and west than to the south and east because the overall statewide food travel distance is shortened by ceding the land to the south of these centers to the NYC foodshed. This distortion takes an extreme form in the case of the Poughkeepsie-Newburgh foodshed (yellow), which extends from the population center as if it were being blown back by the enormous NYC food demand. Conversely, when a population center is relatively isolated, as in the case of Rochester and Buffalo, its potential foodshed spreads more evenly because it is limited by natural barriers rather than by competition with other cities.

This single example doesn’t begin to do justice to the resource provided by the model. I urge people interested in exploring the model further to check it out online:

http://www.cals.cornell.edu/cals/css/extension/foodshed-mapping.cfm

Our local foodsheds

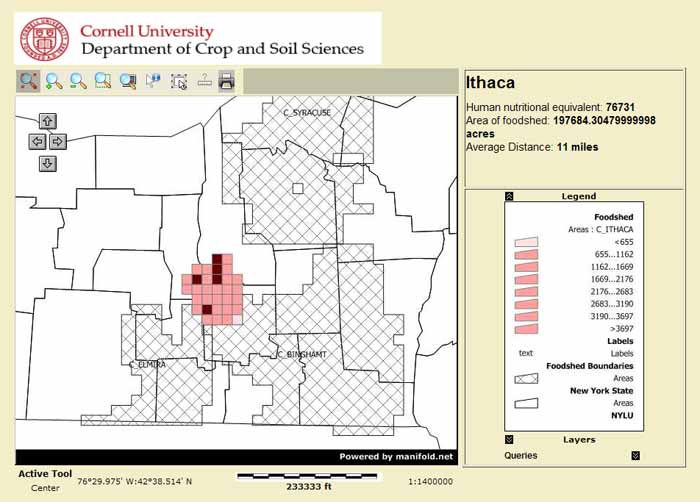

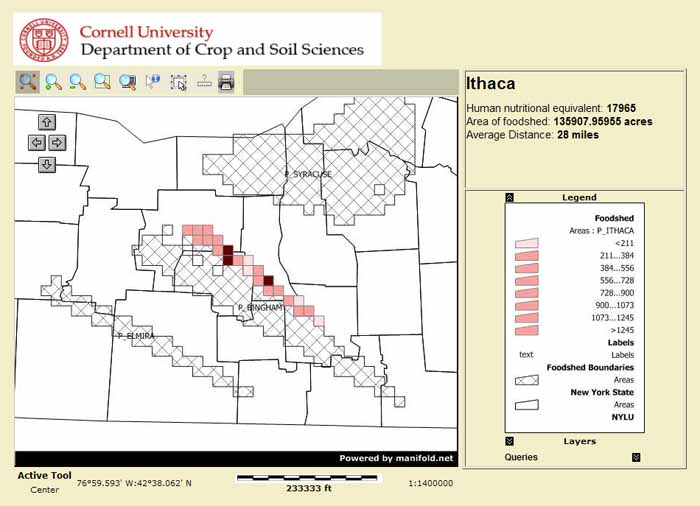

Below are screen captures of two maps generated by the Cornell tool for the Ithaca foodshed, one map for cropland (annual crops) and one for grassland (perennial crops), with the outlines of the corresponding Syracuse, Binghamton, and Elmira foodsheds shown for comparison.

According to the model, in a distribution system that used all available NYS agricultural land, provided a certain balanced diet to everyone, and optimized statewide food distances, Ithaca’s food from cropland (Figure 7) would travel an average of just 11 miles, and its food from grassland (Figure 8) would travel an average of 25. In neither case, however, would that locally sourced food satisfy all the food needs of the Ithaca area population (estimated at 95,000 persons, which includes the Ithaca Urbanized Area plus nearby surrounding rural populations). The model shows that the optimized locally sourced food from cropland would fully supply the cropland component of the assumed diet for about 81 percent of the local population (76731/95000), whereas the locally sourced food from grassland would supply only about 19 percent of that dietary component (17965/95000). This illustrates in detail the conclusion reached in the TCLocal.org article that Dr. Peters published here in April: only about half of our food supply in Tompkins County would come from local sources if food was distributed in a way that minimized food miles for the entire state.

The effect of the immense NYC demand for food on the shape of our optimized foodshed is clear even at this distance from the city; both of Ithaca’s foodsheds lie entirely to the west and north of the population center, extending in the case of grassland across several adjacent counties. Also apparent from these maps is the basis of the model on potential agricultural land rather than the land that’s in production right now; anyone familiar with the areas included in these foodsheds knows that in fact much of the land shown as the potential source of our local food is not now actually in production. The need to preserve currently idle agricultural land north and west of Ithaca for future use has important implications for zoning and land use policy in in our area; as the cost of transportation grows, this is where much of our food will have to come from.

Figure 7. Potential optimized Ithaca cropland foodshed. (Click for larger image.)

Figure 8. Potential optimized Ithaca grassland foodshed. (Click for larger image.)

Where to be a locavore

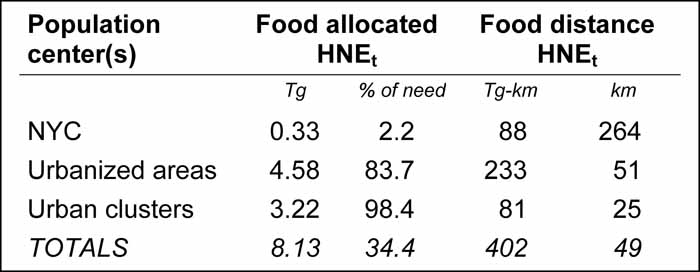

The table in Figure 9 below provides one answer to the question, “how much of New York’s food can be provided locally?” The answer is: it depends on where you live.

Figure 9. Summary of model output. (Click for larger image.)

The table lists three categories of NYS population centers (using terminology from the U.S. Census) in order of the amount of food in Tg (millions of metric tons) they receive within the model. First, of course, is New York City, which is in a category by itself. In this model — which, it must be remembered, optimizes food distances for the whole state — NYC would get just 2.2 percent of its total from food produced within the state, and that food would have to come from an average of 264 km away. The next biggest population centers, the “urbanized areas,” would get 84 percent of their food from inside the state, and that would come on average from 51 km away. And the smallest population centers (excluding the seven very smallest, as noted above), could get virtually all their food needs met from within the state, and the food could come on average from just 25 km away.

Bottom line for the state as a whole: Given the diet assumed for the study, if all agricultural land were in use, and food distribution were optimized to minimize the total distance that food travels, New York State could get 34 percent of its food needs met from within the state, and that food would travel an average distance of 49 km to each consumer.

You’ll notice that the 34 percent figure differs a little from the results of the 2006 study, due no doubt to differences between the two studies in assumptions and methodology. The difference isn’t enough to change the basic picture and in fact reinforces it by coming at it from a different angle, but it’s obvious that the results provided by a model like this depend to a large extent on a complex set of assumptions. The authors point out several ways in which the model does not take into account real-world factors (geographic limitations, agricultural specialization, details of the food processing workflow, economies of scale, etc.) and note that optimizing for food miles does not necessarily optimize for greenhouse gas emissions or energy inputs. Nevertheless, one conclusion stands out fairly clearly. Outside of the NYC area, most population centers in the state could meet all, or nearly all, of their needs from food produced within the state. But NYC, if it depended on food produced within the state, would go largely unfed.

The study boils the results down to what I would call the good news and the bad news. The good news is that “NYS may be able to significantly reduce the distance food travels” to an average far less than the 1300 miles often cited as the distance from farm to consumer in the U.S. The bad news is that “feeding big cities may require food to travel great distances.”

Peters et al. don’t draw out the implications of that last point, but I will: People living in NYC are going to be paying an awful lot more for food as we begin to move down the energy descent slope, and it would be better for them if they started to relocate back to the small towns upstate that have seen their populations decline over the last half century. To rephrase the old saying, NYC is a nice place to visit, but I wouldn’t want to try to survive there.

Notes

[1] Anyone who wants to check my figures or apply this method to other states can find a scan of the entire 1900 census abstract at http://www.ibiblio.org/tcrp/src/1900census.pdf (this 66 MB file is best downloaded before viewing).

[2] Peters, C. J., J. L. Wilkins, and G. W. Fick. Testing a complete-diet model for estimating the land resource requirements of food consumption and agricultural carrying capacity: The New York State example. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 22(2); 145-153.

[3] Peters, C. J., N. L. Bills, A. J. Lembo, J. L. Wilkins, and G. W. Fick. Mapping potential foodsheds in New York State: A spatial model for evaluating the capacity to localize food production. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 24(1); 72-84.

[4] Except for two screen shots (Figures 7 and 8), all the illustrations in this article come from a presentation given by Dr. Peters at the conference “Planning for Farms, Food, and Energy in Central New York” sponsored by the American Farmland Trust 25 March 2009 in Syracuse. I am indebted to conference organizer Judy Wright for a copy of the presentation slides. Most of the figures can be magnified for a better view.

Categories

agriculture11 Comments

Interesting food for thought. Some more thoughts:

If we want people to leave NYC for rural areas, then some questions to ponder might be:

-How would this be economically viable for people? How could they afford to move, and live in economically depressed areas?

-How do we deal with cultural issues? Many people are MUCH more comfortable in NYC than the rest of the state due to their race/culture. Why should/would people move to areas where they are looked at warily, and these issues are not discussed? Same may be true for other groups of people.

-Are apartments more sustainable than houses, since people use less space?

It is also disappointing that the discussion of animal agriculture treats animals like commodities instead of sentient beings with an interest in whatever we decide to do. Efficiency doesn't grapple with possible ethical issues. That being said, it seems that "factory farms" are most efficient in certain situations, due to economies of scale, especially when the animals are fed grass instead of corn. A community may still decide against this.

We might also want to consider prioritizing foods that store well with minimal processing, like dry beans.

The industrial agriculture that provides the data for the Cornell studies is relatively monocultural, with each product being produced in splendid, specialized isolation, even on the same farm. The data thus do not reflect the potential of integrated agroecosystem design to capture synergies that can raise the carrying capacity of the land. For example, the interdependencies between two key land use categories, perennial grassland and cropland, are considered only to determine “which category of land is limiting to food production.” Full integration of perennial-fed livestock and cropping into one system can generate fertility, energy and other valuable inputs that will permit farmers to replace external, fossil-fueled inputs. In an era of increasingly unaffordable external inputs, the higher carrying capacity of integrated systems relative to today’s industrial farms will become dramatically evident as the latter are driven out of business, effectively reducing their carrying capacity to zero. I will explore the synergistic potential of integrated systems in an upcoming contribution to the TCLocal article series.

In common with many today who cling to options that are now beginning to close, Anna’s comment does not seem to want to get Jon’s point, that relocation from NYC in the future will not be a matter of choice. Retaining urban cultural and other “comforts” will not be an option when survival means getting to a place where one can eat.

Likewise, if treating animals like sentient beings means not eating them or otherwise using them on farms, I suggest that sentiment is a luxury rarely permitted in the whole history of mankind, a luxury best regarded as a fleeting abnormality of late modern urban culture, as I suspect coming decades will reveal.

I visited the eminent Physicist, Freeman Dyson, last Friday and one of the topics that came up during our conversation was that the fields around the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, NJ have been significantly re-forested since they stopped being used for hay fields to feed the horses in NYC. So, a complete foodshed for NYC itself would have to include "the garden state," even if most of its fertile land has been lost to development in the years since WWII. This relates to what Jon wisely pointed out, that "NYC, if it depended on food produced within the state, would go largely unfed."

On an even darker note, however, in 2003 I did a brief project for one of my classes at Johns Hopkins University, which I would characterize as merely "back-of-the-envelope" calculation (some of which was based on data from various Cornell University reports). No matter how I came at it, I was forced to conclude that the carrying capacity of the entire planet is only about 2 billion people. And yet, we presently have over 6 billion human beings and are predicted to be headed toward 12 billion. Since then, I've honestly tried not to think about that too much because it's very depressing.

It reminds me of the first day of orientation at engineering school, during which one speaker said: "Look to your left and look to your right. In four years, only one of you will still be here." Though now it's not that the 2 absent people will have merely moved on to study something else. They are likely to be starving or dead.

As an engineer, I feel that people are relying on my colleagues and I to figure it all out so that everyone can continue to enjoy the pre-peak oil party. Yet, every month I'm in conference calls listening to some of the smartest people in the country fret about the impossibility of continuing the pre-peak oil party (though they describe it in different terms) regardless of which energy strategy we pursue. Wind, solar and biofuels won't do it. Nuclear, coal and hydrogen won't do it. Natural gas -- which is used to make fertilizers -- is a non-renewable resource too and probably should be saved to make food rather than burned for heating, transportation and electricity production.

Drastic conservation ... that won't continue the party, but it might allow for survival and even "contented survival" to quote one of my favorite architects, Jay Shafer of the Tumbleweed Tiny House Company. However, drastic conservation is politically unpopular. It's not even popular with the engineers because you can't really build and sell conservation, anymore than you can sell sleep and exercise for better health.

I've seen an ad campaign somewhere saying that a new element, "Hu" for human, will essentially save us all. I'm hopeful that they are right, though perhaps in a different manner than the ad campaigners imagine. For example, perhaps we will discover that the greatest strength of "Hu" is in person-to-person relationships, which are presently under-appreciated by many.

Definitely, we're going to have to get by with less material goods and we'll have to convert lawns to food producing centers with gardens and edible landscaping such as "fruit cocktail" trees, which are beautiful AND useful.

The issue of feeding ourselves is a huge one to tackle and I'm very glad to have the information in this article which I can now use in place of some of my "hunches" and "back-of-the-envelope" calculations. I'm hopeful that we have enough time to use the information so that we and future generations can live better, happier and more contented lives -- which, of course, is predicated upon being able to meet basic needs such as food.

Thank you.

Anna has interesting points and certainly they are factors to consider for a person living in the city and contemplating moving to a more rural area. Having lived in suburban and urban areas myself, and having experienced the wrong end of a prejudiced mob in rural place, permanently moving to a rural place does seem a bit intimidating to me too. However, I also experienced another such mob in an urban place.

So: I would say that it's better to move now, rather than waiting until later. And that is in fact what I mean to do very soon -- perhaps as soon as this coming August. Even with the property market depressed, it's likely that upstate and southern tier property is still affordable even for a person who has to take a loss in selling a downstate property.

Also, relating back to my earlier comment about human relationships, if city folks start looking now, they can find a place that is more friendly for them and establish good relationships *before* a major upheaval. As I see it, waiting only increases the chances that bad things will happen. For example, I've heard rumors that there are militias upstate who are preparing to blow up parts of I-87 to prevent NYC/NJ refugees from coming upstate. In fact, they mean to prevent people from NYC/NJ from accessing their weekend retreats too.

While it may not be possible to build relationships with those kinds of people, there are more inclusively-minded folks in places such as Ithaca.

In addition, it is possible to develop job options now that will help support a person in the transition from city to rural economies. A friend of mine used his contacts to continue working as an editor as his family moved upstate and bought a B & B, which is still doing alright even in this economy, as there are few hotel options nearby. For myself, it took about a year until I found "do-from-anywhere-with-internet" employment. My husband and I are still working on learning skills for post-peak oil life. Likely, I will do more gardening/farming, teaching and carpentry, while he will develop his nursing/health care skills such that he may one day be the local equivalent of a "country doctor."

It takes time to find a new place to live, new employment, etc. And it takes time to establish a homestead. I recall reading that it requires about 10 years of work to develop a really good garden plot with compost, and I know for sure that most fruit trees and bushes don't really begin producing until 3 years after planting.

So, the best advice I can give is: start now! It can seem pretty overwhelming to tackle all at once, but there are a lot of resources to help you on your way. For example, the most positive website I've found so far is www dot postpeakliving dot com . The first step that they list for preparation is: "Take a deep breath — we've been where you are now! Believe us, the more you prepare, the more confident you will feel that you can handle peak oil."

Then, you can work your way through their guide book. :)

Oh about the sustainability of apartments vs houses: I would say that it entirely depends on the house and how it is used. Some intentional communities listed at www dot ic dot org are groups of people sharing one house. Many are in cities, but some are in rural and suburban areas. If you don't want to share a kitchen and bathroom with other people, try a co-housing place like the Ecovillage at Ithaca.

If a group that you are racially/culturally comfortable with doesn't exist, try starting your own. I've heard that there is a developing intentional community in Vermont established by folks who call themselves Radical Fairies.

Which reminds me of one other thing that you said: "Efficiency doesn't grapple with possible ethical issues." I've heard that the Nazis sent gay people to concentration camps for what amounted to a twisted devotion to efficiency. I think it is wise to be mindful of potential ethical pitfalls in choosing efficiency. For example, this month's Johns Hopkins Magazine bears a leading article titled, "Farmacology: Industrial agriculture feeds antibiotics to farm animals. Is it time to stop?" Um ... yeah!

For myself and my family, I'm more comfortable with a diet that relies on vegetables, eggs and milk with occasional fish, chicken, etc. I think eating meat can be done well and with respect, similar to the traditions of the Native Americans and, if I'm not mistaken, similar to the traditions of Jewish people. Factory farms, however, do not meet the standard of "done well and with respect."

And, of course, I respect the choice of people who do not eat meat. Plus, there are certainly many thousands of vegetarians in India and elsewhere who seem to live well enough without meat. I suppose the long term viability of being a vegetarian depends somewhat on climate and geographic factors. So again, choosing the right place to move to -- and soon -- seems like the best approach.

Best wishes,

Crystal

Jan Quarles said:

One often "proves" what one aims to prove. I didn't see any mention of a BIO-INTENSIVE approach, as in John Jeavons' "How to Grow More Vegetables Than You Ever Thought Possible on Less Land Than You Can Imagine." Neither did I see any mention of vertical gardening, which requires far less land than traditional horizontal farming. When combined with the right types of vegetables that you can harvest for several months, like the hybrid cherry tomato "Sungold" that produces fruit from July to October, vertical gardening has great potential to change the Cornell equations.

Is there any mention of PERMACULTURE in the Cornell study, or the value of protein per acre of a NUT orchard? France Moore Lappe, in her 1970s bestseller "Diet for a Small Planet," took a "systems thinking approach" and proved that a vegetarian diet based on specific combinations of beans and grains, or grains and nuts, uses far less land per pound of protein than a meat-based diet. The world population has doubled since JFK was President, so all the more reason why we need studies that go beyond Cornell's, to include approaches that are what I call "land-frugal:" bio-intensive, permaculture, selection of specific varieties (like fava or soy) and specific food combinations. I would bet these studies would produce equally compelling conclusions in favor of a vegetarian diet, refuting Cornell's.

Karl North said, "if treating animals like sentient beings means not eating them or otherwise using them on farms, I suggest that sentiment is a luxury rarely permitted in the whole history of mankind, a luxury best regarded as a fleeting abnormality of late modern urban culture, as I suspect coming decades will reveal."

This is such a sad thing to hear, calling compassion for sentient beings "sentiment." When we're aiming for sustainability, we can't leave ethical considerations behind. Would folks consider it acceptable to, in the name of efficiency, use slave labor on Tompkins County farms? Why then do we consider it essential to continue impregnating, confining, and slaughtering animals for our convenience?

Just because something is done traditionally, and is beneficial and useful to those in power, doesn't mean that it's ethical or desirable. Maybe as we look to the future, we should be stretching our minds a bit farther toward building a world that's healthy and equitable for all species, not just our own.

These studies are quite useful, but they only begin to examine the possible ways that our food system could adjust to energy descent. Jan is certainly correct in pointing out that Peters et al are using current production paradigms and current arable land under cultivation as parameters. Both these are unlikely to continue as-is in an expensive-oil future.

We desperately need foodshed research that also considers agricultural production methods as a variable. And, of course, an underlying assumption of Peters' study is that it would be more difficult to convince a NYS farmer to farm differently than it would be to convince a NYS eater to eat differently. True, farmers are stubborn (and Cornell Agriculture profs are REALLY stubborn), but, expensive oil is likely to cajole everyone into making some changes in MO. In particular, better assessments of the potential of agroforestry and urban agriculture (including rooftop food production facilities) to contribute to total foodstuffs produced is needed.

One thing that Peters' work does address is the fact that soils that are not practical for production of vegetables, fruits and grains may be very capable of producing grass-fed meat animals. Religious convictions aside, many if not most Americans include meat in their diets. Lappe's analysis does not distinguish between soils-- a lapse that is also forgivable, for the same reason that Peters' failure to consider production paradigm is forgivable: you simply can't consider too many variables at the same time. What is the best and most efficient means of feeding our population in an age of lower fossil fuel availability is a complex problem that will require a lot of thought, study and discussion. All simple solutions are likely wrong. All solutions that assume that people will make needed changes in an orderly way are likely too optimistic. All solutions that assume that people will be incapable of any adaptation are likely too pessimistic.

We live, as they say, in interesting times.

Crystal Heshmat said:

If I remember correctly, that language actually came almost verbatim from one of the Cornell studies, and I probably should have noted that in the text. The sentence quoted by Crystal is not an exact quote but pretty close; it should read, "But according to Peters et al., NYC, if it depended on food produced within the state, would go largely unfed." My apologies for the omission.

Jon

The larger issue is transporting food and surviving in the New York after the last power blackout

According to energy investment banker Matthew Simmons and other independent analysts, global oil production is now declining, from 74 million barrels per day to 60 million barrels per day by 2015. During the same time demand will increase 14%.

This is equivalent to a 33% drop in 7 years. No one can reverse this trend, nor can we conserve our way out of this catastrophe. Because the demand for oil is so high, it will always be higher than production; thus the depletion rate will continue until all recoverable oil is extracted.

Alternatives will not even begin to fill the gap. And most alternatives yield electric power, but we need liquid fuels for tractors/combines, 18 wheel trucks, trains, ships, and mining equipment.

We are facing the collapse of the highways that depend on diesel trucks for maintenance of bridges, cleaning culverts to avoid road washouts, snow plowing, roadbed and surface repair. When the highways fail, so will the power grid, as highways carry the parts, transformers, steel for pylons, and high tension cables, all from far away. With the highways out, there will be no food coming in from "outside," and without the power grid virtually nothing works, including home heating, pumping of gasoline and diesel, airports, communications, and automated systems.

This is documented in a free 48 page report that can be downloaded, website posted, distributed, and emailed: http://www.peakoilassociates.com/POAnalysis.html

In June I took a trip to Albany to talk to 3 audiences on Peak Oil impacts. In the group that invited me, the Capital Regional Energy Forum CREF), is a physicist who teaches solar energy at a major university, and who had served in the Peace Corps.

He has solar powered just about everything, including a solar powered canoe which we went for long ride in on a lake in the Adirondacks, and a PV solar powered house and pump for his well. He repairs about everything on his house himself and he heats much with passive solar. So the guy knows his stuff. He is no ivory tower academic.

We talked for hours about survival in the northeast after the last power blackout.

It looks "challenging."

Eventually batteries and even the solar panels deteriorate. He thinks that he could store dry batteries with the liquid stored in glass and thus make "new batteries" after they conk out. But eventually the batteries and solar panels give out.

Cutting and moving wood without trucks, horses, and wagons will be a major effort and very time consuming. There are not many horses around and it will take decades to breed enough horses to go around. Horses require food, care, vets, and medicine. No one is making wagons these days locally.

Wood stoves break, just like everything else. You could keep one or 2 extras, but eventually you have none and can't get more, because there is no transportation on the highways.

Asphalt roof shingles need to be replaced, and houses need to be painted and maintained.

Food must be grown in with a short growing season, and all of the farm stuff that used to be in a 1890 Sears catalog is no longer available. Last summer I took a tour of a farm and saw how dependent farming is on oil -- transportation and manufacture of plastic feeding bowls, containers to store grains/feeds, straw, roofs for animals and storage areas, wire, rope, wood boards, cement, fencing, antibiotics for animals, asphalt shingles etc. Seed and hardware used to be available at the local hardware store, no more.

Then there is clothing which is manufactured and transported from afar. Making cloth is a major operation from growing cotton to making cloth. I have studied the textile mills of Lowell National Historical Park in Lowell, MA for years, as I used it as an example of the confluence of capital, technology, and labor for a course I taught on Global Urban Politics at the University of New Hampshire. I know that the parts in those factories were manufactured in many places with a vast transportation network. After the last power blackout, those factories will not be built again. And there are not many sheep around, nor animals for making leather clothes. Eventually down coats and comforters wear out, as do blankets. It sounds like just keeping warm will be a major problem.

Potable water is another problem, and sanitation also.

And there will be no modern pharmacies or hospitals.

After auto and air transport end (which could be next week if there is some "untoward activity" in the Middle East), there will be no way of getting here, or from here to there. Bus and train reservations will be backed up for years. You know the old Maine joke, "can you get there from here?" Well this time the answer will be no you can't. I keep reading in the newspapers that some of the folks over there in the Middle East are tired of others getting most of that oil, and that they are trying to shut down the flow of oil to us (:

Wasn't it that guy Murphy who said that if something can go wrong it will.

When the music stops (that is when air and automobile transportation ends) where you are is important, because that is pretty much where you will stay.

Clifford J. Wirth, Ph.D.

http://survivingpeakoil.blogspot.com/

A better question might have been:

Can New York State Feed On Itself?

It is very interesting to read your post. In future green revolution needed to meet the people's food necessities.