Heating with Biomass in Tompkins County

by Krys Cail and Tony Nekut

This article continues the discussion of heating with local biomass begun in our October feature, “Burning Transitions” (http://tclocal.org/2009/10/burning_transitions.html). There it was noted that the best application for local biomass energy is combustion for space heating, possibly coupled with distributed CHP (combined heat and power) electricity generation, and that these technologies are, for the most part, already developed and available in the form of high-efficiency gasifying boilers and pellet stoves.

Work is required along the entire supply chain (growing, harvesting, processing, distribution, and utilization) if local biomass energy is going play a significant role in Tompkins County’s energy future. The traditional economic stakeholders are a diverse group of mutually dependent players (landowners, loggers, foresters, farmers, manufacturers, fuel retailers, and consumers), each requiring commitment from the others to make the system work. Leadership and planning are essential to moving beyond gridlock by demonstrating how, through cooperation, everyone along the chain stands to benefit. Fortunately, there are a variety of case histories and other resources that have been developed in recent decades that render this demonstration somewhat easier.

Barring unforeseen breakthroughs in energy technology, it seems clear that this resource will indeed be developed. Local biomass is already cost competitive with fossil fuels for space heating, and its economic viability will only improve as fossil fuel prices continue to rise. The time has therefore arrived to begin development, because time will be required build the needed infrastructure.

The scale of the local biomass development challenge

Every form of biomass yields about 16 million BTUs per dry ton when burned. Sustainable annual biomass productivity ranges from about 0.5 dry tons per acre for our local forests to 5 dry tons per acre for some locally suited energy crops. These productivities represent conversion efficiencies from solar radiant energy to stored chemical energy of about 0.1 to 1 percent. If half of Tompkins County’s 300,000 acre land area were committed to growing biomass, the annual per capita energy production would range from about 12 to 120 million BTUs. (See the discussion of County land cover in the October “Burning Transitions” article.) By comparison, current (2007) statewide annual per capita primary energy consumption is 219 million BTUs. In other words, the amount of biomass energy we could get from our land even in relatively rural Tompkins County would yield nowhere near our total energy needs.

Meeting our heating needs is another matter. Each household in the County uses about 100 million BTUs annually for water and space heating; this is about 43 million BTUs annually per capita — approaching the range of sustainable large-scale local production. Adding the wholesale implementation of residential energy efficiency measures would bring total heating energy self-sufficiency within reach. Ed Marx, Tompkins County Commissioner of Planning and Public Works, has been quoted as estimating that biomass could heat up to 40 percent of the homes in the county, or even more if homes were super-insulated.

The biomass heating gap

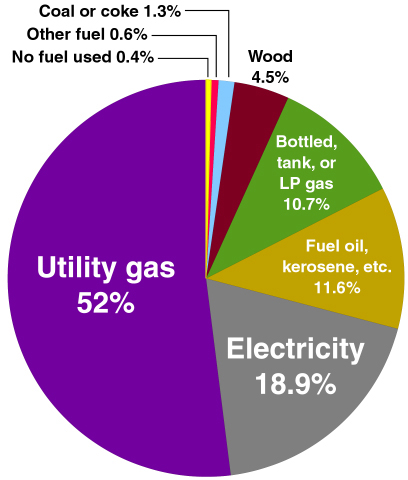

Local biomass energy for heating has enormous potential benefits. It creates jobs, keeps money local, provides energy security, reduces CO2 emissions (locally burned biomass is virtually carbon-neutral), increases carbon sequestration, slows fossil fuel depletion, improves forest and soil health, maintains rural land values, reduces development pressures, creates community ties, and raises community environmental awareness. But fewer than 5 percent of County homes are listed in census data as heated primarily with biomass (cordwood and pellets). For 2008, the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey estimates the percentages shown in the following diagram for heating the 37,749 occupied housing units of Tompkins County.

The apparent lack of interest in heating with wood shown by the 4.5 percent figure is partly an artifact of the way the data is gathered and partly due to active discouragement of wood heat by mortgage lenders and insurance companies.

Wood heat appliances do not enjoy wide acceptance by those who underwrite mortgages and insure homes. Due to the perceived risk of fire, many underwriters of homeowners insurance will not insure properties with wood stoves. (Pellet stoves, which are less likely to cause chimney fires, are a bit more acceptable.) In particular, homes that include rental units — even if the home is also owner-occupied — are very difficult to insure if there is wood-burning equipment in use for heating and the insurer is aware of that fact.

Of course, homeowners insurance is a requirement for any house that has a mortgage. But it is not just the reticence of homeowners insurance underwriters to insure homes with woodstoves that limits use of this technology; there is also a problem associated with wood heat when the lender packages the mortgage for resale on the secondary mortgage market. Despite the worldwide use of this simple technology, burning wood to heat a dwelling is perceived as too risky. Where woodstoves are a secondary, rather than primary, source of heat, this is overlooked. But a home that relies predominantly on wood for its heating source is a home whose purchase will be difficult to finance.

Gaining a more accurate estimate of local trends

This situation — which makes it plausible to add wood heat as a secondary heat source, but difficult to rely on it as a primary heat source — helps explain why the census figures for wood heat seem so low. This is a problem even in the decennial direct counts.

The between-decades estimates suffer from an additional problem: there’s no mechanism for reporting a local trend. Households demographically similar to the various household types in Tompkins County are surveyed at various locations around the country, and the composite picture of their changes is applied to local households with similar characteristics. For instance, if upper-income professional couples with two or fewer children in the home were, for the most part, heating with natural gas across the US, there would be no mechanism for the American Community Survey to read a recent upswing in purchases of woodstoves and pellet stoves among local college and university faculty.

To get a better idea of what’s really happening locally, we had to ask around. The results, while anecdotal, point to just such a trend.

The sales managers of both local woodstove/pellet stove retail outlets indicated that business has been steadily increasing throughout the decade, with particularly noticeable upswings in wood heat appliance purchases when other forms of fuel — particularly fuel oil — experienced price run-ups or price volatility. Both described their typical customers as college professors or other professionals interested in saving money and in helping to conserve non-renewable resources. While families living in more rural and suburban locations were the norm for local wood heat users at the beginning of the decade, the increasing popularity of pellet stoves has resulted in more urban families buying wood heating appliances.

A construction manager at Ithaca Neighborhood Housing Services, which administers a group of NYSERDA programs aimed at green energy for heating, concurred that more urban residents are choosing pellet stoves, and that the help available from NYSERDA resulted in more low- and moderate-income families being able to access affordable financing to add wood heat to their homes.

Another indication of the rising local popularity of wood heat of various sorts is the brisk business that fuel purveyors are doing in cordwood and pellets. The owner-operator of Finger Lakes Firewood, the largest local cordwood dealer, has purchased additional automated equipment to better clean and move his cordwood as his customer base has continued to expand. Ithaca Agway has been using its display sign to advertise pellets, and the Home Depot devoted as much space at the front door to sale-price wood pellets as to the snow blowers.

Industrial uses of wood heat

Wood heat is beginning to appear in local industrial operations, too. For example, US Salt in Watkins Glen is in the process of converting the heating of its large facility on Seneca Lake to biomass.

According to Len Boughton, an engineer with the firm who has been responsible for overseeing the construction and retrofitting, the system, after two years of work, is now in place and operational, but the switch to wood-based fuel will wait till March to allow troubleshooting during a season of less extreme heating demand.

Plant Manager Frank Pastore said that US Salt has contracted with TreeSource Solutions (http://treesourcesolutions.com/) to avoid the management burden of dealing with multiple suppliers. TreeSource is a wholly owned subsidiary of Catalyst Renewables (http://www.catalystrc.com/). Pastore said that he expected the bulk of the fuel to come from local sources, through the Wood Yard that TreeSource has established nearby in Burdett, but that he trusted the contractor to source wood fuel as appropriate in order to maintain a stable and affordable price.

Buying and selling biomass in Burdett

The Wood Yard at the old railroad depot in the Village of Burdett was, in its last incarnation, a steel recycling facility, and many of the buildings are simply being reused “as is” the old depot itself is used as a scalehouse for weighing trucks. The facility includes a large, rambling lot with a gated entrance from State Route 79. The Yard was not officially open the day of our visit, but it’s clear that the facility is used in a number of synergistic ways in addition to providing a means to weigh and store wood intended for use as biomass fuel.

Entrance to the Burdett Wood Yard

A recently constructed pole barn houses a portable bandsaw mill, and some rough-milled lumber showed that the facility is in active use. A large pile of logs awaiting conversion to woodchips was evidence of the yard’s role as a source of fuel, though there was no tub grinder on site. A tub grinder, which can cost up to a million dollars, is typically portable over the road system and will presumably be brought onto the site to process the logs as needed.

Portable bandsaw mill at the Burdett Wood Yard

Arrangements for dropping off wood and arranging payment are made directly with TreeSource Solutions’s buyer, Jack Santamour, who spends most of his time at TreeSource’s facility in the Adirondacks and manages the Burdett yard via telephone with the help of some local employees. TreeSource is currently buying logs by the ton every Friday or by appointment.

Wood awaiting processing by TreeSource Solutions

A cooperative model of biomass production in Danby

One key to sustainable local wood heat in Tompkins County is the creation of a system whereby local landowners can convert otherwise unused or underutilized farm or pasture land to biomass production. The Danby Land Bank Cooperative (http://www.danbylandbank.com/) provides an organization and infrastructure that allows owners of 10 or more acres in the Town of Danby to use their fields and forests (much of it marginal for farming) for grass and wood pellet production.

Built on a classic cooperative model, the goal of the Land Bank is “to unify fragmented and non-farming rural landowners to form a large enough agricultural base to provide economies of scale.” Local members of the co-op lease their land to be harvested of perennial grasses as feedstocks for grass pellets or briquettes; the land is cleared for free, and the owners receive tax credits and, eventually, a share of the profits.

In operation barely a year, the DLBC has already gained 20 owner-members with more than 350 acres devoted to the project. Governance structures are in place, and plans are in the works to incorporate as a legal cooperative. The project, aided by consultation with the County Planning Department and close cooperation with Cornell Cooperative Extension, received major publicity in November with the appearance of a feature article in Rural Cooperatives, a publication of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (www.rurdev.usda.gov/rd/pubs/RuralCoop_NovDec09_Final.pdf).

First hay cutting of the Danby Land Bank Cooperative (photo courtesy of DLBC)

Establishment of a local pelletizing plant has been identified as a key to long-term sustainability and economic viability through reduction of transportation costs. The pellets, which are manufactured by grinding, drying, and extruding raw biomass into a dense, free-flowing fuel of consistent quality that can be efficiently used in inexpensive residential appliances, have a retail market value per dry ton well over twice that of the raw feedstocks. The value added more than covers manufacturing costs, so pelleting can provide an economically viable link between local biomass suppliers and the existing local pellet market.

The DBLC recently joined with Energy Independent Caroline to sponsor Town Hall meetings in Danby and Caroline regarding a company called Community Biomass Energy, which proposes to build a local biomass pelletizing mill on Boiceville Road in Caroline just south of State Route 79. (Disclosure: One of us (Nekut) is a principal in this effort.) See the DBLC’s newsletter (linked from their web site) for details and updates. The December 2009 issue is at http://www.danbylandbank.com/site/resources_files/DLBC_Newsletter_Dec_2009.pdf.

Unresolved issues

Local biomass harvesting and processing hold great promise for reestablishing the county's ability to provide for its own heating needs. However, several issues remain unresolved.

We need to relocalize food production, too. While much of the land in the county that could produce biomass for heating is marginal for raising cultivated crops, a substantial percentage of that land could alternatively serve for rotational grazing of livestock, which is arguably a less-intensive, lower-input use of the same acreage. Thus the optimum allocation of land for biomass production vs. land for grazing or the production of winter hay remains an open question whose eventual resolution will depend on a number of variables that are difficult to predict.

The increased use of biomass for heating will increase economic incentives to harvest wood resources beyond a level that's sustainable. The large-scale reversion of former Central New York farmland to successional forest over the last half century makes it easy to forget how quickly the forest can be cleared again. The establishment of sustainable forest management practices will be essential to the return of biomass heating as a long-range relocalization strategy.

The rediscovery of biomass as a heat source has created a market for American wood chips as far away as Europe. Our region's potential as a major biomass producer also makes it susceptible to the kind of resource exploitation we associate with third-world countries. Heating our homes with local biomass won't succeed if higher prices cause local biomass to be exported rather than used locally.

The need for greater local control over the allocation of our local resources argues for the establishment of biomass harvesting and processing facilities under local management and provides further reason to hope for the success of initiatives such as the Danby Land Bank Cooperative and the proposed Community Biomass Energy facility in Caroline.

Online wood heating resources

Cornell Cooperative Extension has posted an excellent collection of links to articles on firewood resources and heating with wood on their statewide web site at

http://cce.cornell.edu/Environment/Pages/HeatingwithWood.aspx

Categories

energy production