September 2008 Archives

By Katie Quinn-Jacobs

Home preparedness is a complex subject. However, a simple way

to approach it is to focus on four basic elements: energy,

shelter, water and food. Individual circumstances for both the

long and the short term vary, of course, but these core elements

will keep you centered on the most important things first. Whether

you live in an apartment, co-housing, the burbs or a spread in the

countryside, a complete preparedness plan will include all

four.

Home preparedness is a complex subject. However, a simple way

to approach it is to focus on four basic elements: energy,

shelter, water and food. Individual circumstances for both the

long and the short term vary, of course, but these core elements

will keep you centered on the most important things first. Whether

you live in an apartment, co-housing, the burbs or a spread in the

countryside, a complete preparedness plan will include all

four.

Our present culture is predicated on highly centralized interdependencies, like just-in-time warehousing and specialization of services, that are not easy to replicate or extricate yourself from. Since our present lifestyles are products of that system, it’s going to be the rare household — at this stage of the energy descent transition — that is able to be entirely self-sufficient.

Preparedness vs. Survivalism

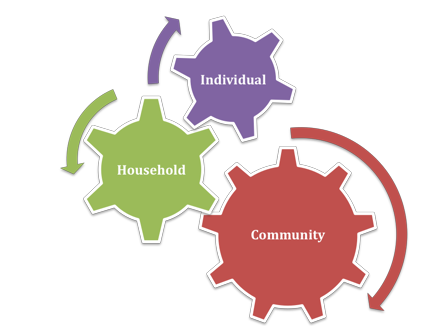

Individual household preparedness, constructed in a social vacuum, isn’t the most valuable long-term goal in any case; building community preparedness based on vibrant and sustainable social and economic structures is. Richard Heinberg’s article on resilient communities (http://www.richardheinberg.com/museletter/192) discusses this topic in more detail. Energy descent demands more individual activism, but not a revisioning of the American rugged individualist. A collective goal, mobilizing our community, is the winning strategy. Attempting to be an island unto yourself, like the “beans, boots and bullets” survivalists, not only raises ethical issues but is impractical as well. Our very nature is to be interdependent communal creatures. It’s easy to be discouraged or outright frustrated with transitioning the commons (or Commons in Ithaca’s case), but that’s the task ahead of us. “We’re all in this together” is not just happy talk; it’s an accurate assessment of our circumstances.

Collective change and community preparedness are the long-term necessities, yet it’s also important to take a look at short-term emergencies that volatility in the oil or gas markets could engender.

Short-Term Preparedness

If there is a regional shortage of gas, or if grocery store supply lines are disrupted or if the electric grid fails, you will want to be prepared. In the event of one or more of these scenarios, grocery stores and gas tanks will empty in a matter of a few days, if not a few hours. The systems that depend on fossil fuels in your home and community will be compromised in short order.

Most households in our area could be prepared to provide their own stored heat, water and food and could have an evacuation plan in place. Such emergency planning has not been a priority in Tompkins County, where floods and earthquakes are rare. And although we, like the rest of the country, are precariously perched on a complex system that requires numerous high-tech, fossil-fuel-powered elements to function properly, we don’t spend much time on contingencies because, for the most part, Tompkins County has been isolated from disaster. Even though many warning signs exist (see http://www.postcarbon.org/), we are no more ready for an abrupt oil or gas shortage than we were for the failure of the levees protecting New Orleans.

But your household can be ready to ride out a short-term emergency. By focusing on the basics — energy, shelter, water and food — you’ll develop a solid preparedness plan. FEMA (http://www.fema.gov/areyouready/index.shtm) recommends three-week supplies of energy, food, and water. These recommendations are based on how long it takes (on average) for relief efforts to reach victims, but you may find it prudent to prepare for a longer period.

Energy

Assess your energy situation first. Identify what critical systems (heat, refrigeration, water) in your home are dependent on electricity and strategize how best to deliver those systems off the grid or think about how you can live without them. If you can’t live without them, then you’ll need to evacuate your home. Many utility appliances, such as heating systems, even if they are oil based and your tank is full, cannot run without electric igniters, fans or pumps.

If you can generate your own electricity, how long will your

system sustain your home? If you rely on a generator, how many

hours of fuel do you have? If you are plugged in to alternative

energy, how long can you keep critical systems (heat,

refrigeration, water) going? How much of your usage will you need

to curtail and how long will your batteries hold out?

If you can generate your own electricity, how long will your

system sustain your home? If you rely on a generator, how many

hours of fuel do you have? If you are plugged in to alternative

energy, how long can you keep critical systems (heat,

refrigeration, water) going? How much of your usage will you need

to curtail and how long will your batteries hold out?

Test your energy plan by simulating a power outage in your home, then make corrections or enhancements to boost your off-the-grid longevity.

Shelter

Historically, lack of heat is the number one reason people are forced to evacuate their homes in the northeast, largely because ice storms or heavy snows bring down power lines. However, fuel shortages or electrical failures aren’t seasonal, and in a post-peak-oil world, we need to be prepared for these infrastructure failures as well as natural disasters. Secondary crises, such as social unrest, gas leaks, and water-borne illness can also be potential concerns if the power outage or shortage is prolonged, as it was in New Orleans in 2005.

Having alternative shelters identified ahead of time will increase your chances of staying safe through the crisis. Assemble a communication list with your family and neighbors, so you can offer each other assistance if needed. Keep a small hand crank radio, so that you can hear public announcements and news bulletins.

Water

After loss of heat, the next reason for evacuation is lack of

water. Storing water is as easy as it is essential. You’ll

need to store 1-2 gallons/person/day for a minimum supply of 21

days, so that works out to be 21-42 gallons/person. (FEMA

recommends a gallon a day per person, but two gallons a day will

give you some cushion for the unexpected.) More information on how

to store water and where to obtain the needed supplies is

available at the PreparedTompkins.org post 2 Gallons A Day

(http://www.preparedtompkins.org/?p=13).

After loss of heat, the next reason for evacuation is lack of

water. Storing water is as easy as it is essential. You’ll

need to store 1-2 gallons/person/day for a minimum supply of 21

days, so that works out to be 21-42 gallons/person. (FEMA

recommends a gallon a day per person, but two gallons a day will

give you some cushion for the unexpected.) More information on how

to store water and where to obtain the needed supplies is

available at the PreparedTompkins.org post 2 Gallons A Day

(http://www.preparedtompkins.org/?p=13).

Sanitation quickly becomes a significant issue, too. A simple 5 gallon bucket (like those used for drywall plaster) can be converted into a toilet. Inexpensive snap-on toilet seats are available through preparedness vendors, like Red Flare, for this purpose. Small air-tight portable toilets with water reservoirs are more expensive, but are also available. Work out where you plan to safely dispose of your waste (this will undoubtedly involve a shovel and an inquiry to your township’s zoning board) as part of your short-term plan.

If you have a drilled well on your property, you may be able to

install a hand pump to use in emergencies. Hand pumps can be

installed on top of the well casing if the residual water level in

the well doesn’t exceed approximately 100

feet. Lehman’s has good information on installing a hand

pump on your well, including a how-to DVD. And Bison sells

stainless steel hand pumps that are manufactured in Maine. For

more information on installing a hand pump on your well, see

Hand Pumps on Drilled Wells (http://www.preparedtompkins.org/?p=119).

If you have a drilled well on your property, you may be able to

install a hand pump to use in emergencies. Hand pumps can be

installed on top of the well casing if the residual water level in

the well doesn’t exceed approximately 100

feet. Lehman’s has good information on installing a hand

pump on your well, including a how-to DVD. And Bison sells

stainless steel hand pumps that are manufactured in Maine. For

more information on installing a hand pump on your well, see

Hand Pumps on Drilled Wells (http://www.preparedtompkins.org/?p=119).

Food

Storing food for short-term emergencies can be done in a number

of ways.  Some people prefer to put aside a portion of their

grocery money to build a supply over time, or you can do it all at

once. You can even purchase rations through preparedness vendors

online, which costs a bit more, but is a good choice for those

pressed for time. Use a food calculator (http://www.preparedtompkins.org/?p=15) to estimate how

many pounds of each food group to put away. Also check out the

posts on the food section of PreparedTompkins.org (http://www.preparedtompkins.org/?cat=4),

including how to pack a “superpail” (http://www.preparedtompkins.org/?p=49).

Some people prefer to put aside a portion of their

grocery money to build a supply over time, or you can do it all at

once. You can even purchase rations through preparedness vendors

online, which costs a bit more, but is a good choice for those

pressed for time. Use a food calculator (http://www.preparedtompkins.org/?p=15) to estimate how

many pounds of each food group to put away. Also check out the

posts on the food section of PreparedTompkins.org (http://www.preparedtompkins.org/?cat=4),

including how to pack a “superpail” (http://www.preparedtompkins.org/?p=49).

Rotate your stock and do an annual inventory. Pick a quiet time of year (perhaps February?) and involve the entire household in the exercise. Not only is it good to share the knowhow and have help with the job of storing food, but if your are not at home during a shortage, there will be at least one other person in your home who understands your food storage system.

Evacuation

Like any part of preparedness planning, arrange for this possibility ahead of time. Ideally, you’ll work out at least two different local scenarios and one outside our region (many disasters are regional, and leaving the area, if possible, may be the best course of action). Whether you plan to go to a neighbor’s, a family member’s or a public space, consider how you will get there. Wherever you end up, it needs to be accessible, safe and equipped with the basic necessities: energy, shelter, water and food.

Have an Emergency Evacuation Kit (EEK) complete with a communication list ready to go. Although your EEK can be made out of almost any storage container, more often than not people use backpacks for their EEKs (one for each member of the household), since they are designed to store gear, are highly portable and leave your hands free while you carry them. Putting these together in advance is important: you’ll be clearer-headed about what to put in your EEK and who you need to add to your call list if you’re not embroiled in an ongoing emergency.

Make the go/no-go decision before the decision is made for you. If you think you may need to evacuate your home, be sure not to wait too long. You’ll need time to secure your home systems (drain water pipes, turn off gas valves, gather current banking records, notify family members), and the longer you delay, the more likely that your options may become limited: roads may close or darkness may make leaving harder or you may face a worsening security situation.

New Interdependencies

Preparedness, whether for the long or short term, is an interconnected process that begins with individual awareness, but it must be followed by concrete practical steps. We cannot think our way out of the triple crises of energy, environment and economy. Whatever anxieties preparedness can evoke, it also bestows piece of mind once your plan is in place, and it will lead you in new and unexpected directions along the way. Your short-term plan may inspire you in ways you hadn’t thought about prior to doing this work and introduce you to people you wouldn’t have otherwise met.

Grassroots (bottom-up) change has the capacity to rework not only our lives, but our larger community as well. As we put our individual plans into action, our community begins to shift too: grocery stores become accustomed to bulk buyers, green jobs in alternative energy and building grow, humanure provisions work their way into zoning laws, local farms and urban gardens flourish, plumbers gain expertise at installing hand pumps, schools teach preparedness planning in class, sewing (http://www.sew-green.org/) and food preservation groups (http://www.preparedtompkins.org/?page_id=60) form, etc.

Myriad networks of people pool their knowledge and resources to create an interdependent lifestyle, not based on long distance just-in-time warehousing (in big-box stores or at home) and centralized specialization, but on local needs for goods and services. Although we are very fortunate here in Tompkins County, since this long-term process is already underway, we must not turn a blind eye to the possibility of short-term emergencies during these volatile times lest we find ourselves wanting.