July 2008 Archives

[This is the second part of a two-part series. Post-Peak Land Use Part 1: Ecocities appeared previously. As usual, we invite your comments. A Land use glossary explains some of the terms used in these articles.]

By Josh Dolan

A sustainable city requires a balanced relationship with its neighboring rural areas. Moving toward a higher urban density while achieving a lower overall regional density will require transformation in both urban and rural areas. Food, fuel, and other human uses are important factors when considering rural land use. Housing and employment can be added in nodal developments close to prime agricultural soils and diverse forests.

Our region is known for its diverse agricultural products, including grapes, wine, orchard crops, dairy products, beef, and organic vegetables. Most agricultural land should shift away from acre-hungry factory farm, feedlot-style beef, dairy, and corn production toward more intensively managed field crops for human consumption and grass-fed small-scale meat production. The goal should be to sustainably produce as many calories per acre as possible while increasing productivity and employment. Many historic farms and prime soils are underused. Undermaintained land and agricultural buildings can be restored and brought back into production. This will create new and revitalized spaces which can be utilized as workshops to create diverse products.

Many of these farms can be updated for the 21st century by integrating permaculture design with highly diverse and resilient farm ecosystems. Diverse farm models can also be used to revitalize the rural economy by creating many more niches for humans within the landscape. As we shift from a high available energy service-based economy to a low-energy material economy, much of the energy currently gained through the use of fossil fuels will have to be replaced with labor-intensive human power. Systems should be created to link willing young farmers with land, to incubate rural land-based businesses, and to assist groups hoping to create cooperative farms and ecovillages.

Well-managed forests can provide a wide array of products. Many area forests are lacking good management and as a result are less healthy, more crowded, and less diverse than they could be. Popular education for rural landowners and farmers can instill better management practices, and cooperatively owned portable saw mills and forestry tools can help them add value to wood from their land. Programs to increase land access, especially access to forested land, can link urban residents with land in the country. Agroforestry techniques can increase diversity in forests and produce an income from lumber, value-added wood products, fruits and nuts, edible natives and fungi, and medicinal products.

Recreational uses such as hiking, biking, hunting, and fishing can help preserve rural land and important habitat. Riparian buffers along streams and rivers can reduce turbidity, reduce soil erosion, and integrate recreational uses. These buffers can also provide forest products, habitat, and wildlife corridors. Buffers of a minimum of one hundred feet are highly recommended for all creeks, but depending on soils and slopes, buffers could be much wider. Buffer strips can be managed by farmers and community projects. Steep slopes currently tilled annually should be converted to permanent cover such as nutteries and orchards, as well as coppice crops such as willow and poplar for biomass fuel.

The Conservation Village

The basis of rural life should be conservation villages: ecovillages from 50 to 200 households in size.

www.cascadeagenda.com/strategies/conservationvillages

These villages should be located within a ten-minute walk of major transit stops and should be designed using the same principles as urban environments. Higher density rural deveopment will also mean more feasible car sharing. Rather than the suburban model of development — which has an extremely low density, energy-wasting housing, and high dependence on auto-based transportation — these new developments should be urban and walkable in character, they should feature energy-conserving naturally built housing, and residents should work on site as much as possible. By retrofitting and reusing existing buildings, their embodied energy will be preserved.

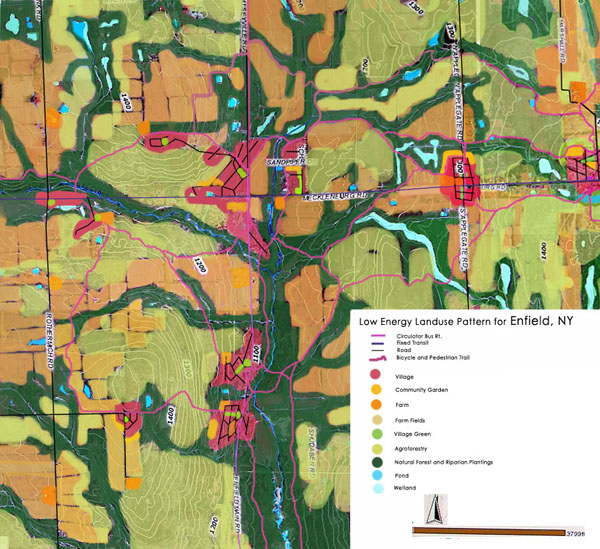

The dark green of streams and wetland areas forms the

backbone of the new landuse pattern. Nestled between the fingers

of naturalized riparian corridors lies the productive landscape of

forests, agroforestry plantings, grazing land and other farm

fields. Farms are scattered throughout the landscape and,

finally, villages are layed out along the dark purple fixed

transit line and the light purple cirulator bus corridor. Pink

pedestrian and bicycle trails connect the villages to each other

and with the landscape.

Applying compact nodal development patterns greatly contracts overall development and, thus, fuel and energy use. Again, nodal development should always be linked with fixed transit and should occur in existing major transit corridors. Compact development would include multi-family housing with live-work features. Natural building techniques, proper placement and orientation of new buildings, and culturally sensitive design will create timeless and efficient towns that will be more desirable to live in, while efficiently sheltering residents. Energy-sucking low-density housing can gradually be dismantled or integrated into new village centers; using Transfer of Development Rights, financial and lifestyle incentives, and taxation, county policy can shift residential land use into a much more environmentally sound pattern. Farm land can be freed up and many forests allowed to grow back, becoming a source for sustainable energy far into the future. Here is an image of the Chrysalis Concordium (chrysalisconcordium.org), a car-free village concept from Rob Morache.

The car-free village nestled within the farm landscape. (Image by Rob Morache)

Zonation, a common design consideration in permaculture, orients high-activity gardening and vegetable farming close to each of the conservation villages. Orchards and grazing are slightly farther away and forestry operations farther still, along with irrigation and aquaculture ponds. Land of high biological diversity and health surrounds the village, with some land remaining wild and used for wildlife and low-impact recreation.

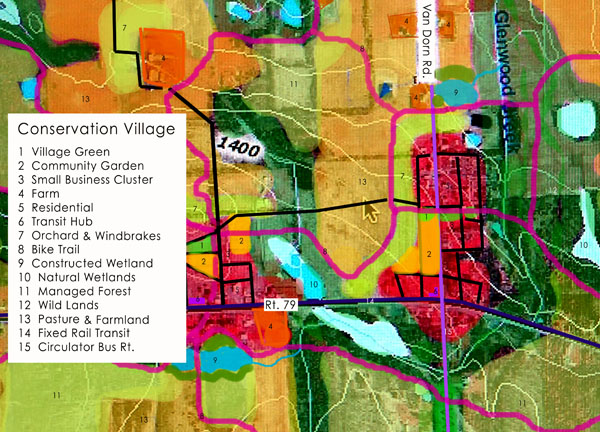

The Conservation Village assists in the preservation

of both wild land and farm land, nestled in the midst of both. By

putting the village back in the context of the country, residents

are put in direct proximity of a productive landscape. This

allows for a return to a material-based economy. Notice how the

village integrates the existing built environment into its fabric

and how solar aspect and landform play into village sites.

Efficient water catchment and conservation will be a high priority. Protection of creeks, riparian habitat, slopes and sensitive environmental features, wildlife corridors, and greenbelts allows for a large increase in many under-recognized and underappreciated natural services such as climate control and erosion control as well as the well-being provided to humans by intact natural areas. Public access with bike and hiking paths can allow any resident easy access and potential fitness benefits.

Ponds can catch and store water, and thus energy, high in the landscape. Through contouring and land-forming techniques such as keyline, water can be evenly distributed throughout the landscape. Pervious pavements and surface drainage within the conservation village will solve most conventional drainage problems and create beautiful water features within the residential area. Greywater can be treated on-site in constructed wetlands and living machines, then recycled in orchards and woody biomass plantings.

Energy can be produced entirely on site with a surplus for export to the city. Active solar should be an element on each building. Higher elevations are best for wind turbines and for storing water. Developments that straddle rivers and streams can take advantage of small-scale electrical hydropower and mechanical hydropower for milling wood, grinding grain, and other uses. Biofuels have multiple uses on the farm and in the village, many of which could be extracted from long-lived and productive crops such as nut trees. Wood can be used efficiently in the home and can also be used in gasification to produce natural gas for cooking; the char by-product can be used as a soil amendment that traps carbon in the soil for centuries. Wood can also boil water to create steam in a boiler facility that is then distributed to heat the entire development; this is called district heating. Wire, water pipes, tools, and vehicles will all be used more efficiently in the compact development. The total energy savings resulting from better development will be substantial and come from many sectors.

Each of the towns in Tompkins County would feature new nodal developments surrounding an enhanced, higher density town center. A transit connection in the town center would connect the rural population to downtown Ithaca and the University, College, downtown jobs, and downtown culture. The opportunity to develop a craft-based utilitarian economy would arise from villages' proximity to the land. Farmers' and crafters' markets in the centers will be the cornerstones of local life and generate significant tourism. Public-private partnerships can be created to establish not-for-profit business incubators, which will help to develop the physical infastructure of the village center and the village economy itself.

As we face the challenges of climate change and peak oil, we would do well to remember that all changes are not necessarily bad. The potential to transform our society for the better is at hand. By working together, we can do our part to reduce American energy consumption.

Previous article: Ecocities.

Land use glossary

Land use bibliography

Land use resources

By Josh Dolan

[This is the first part of a two-part series. Post-Peak Land Use Part 2: The Country will appear in two weeks. As usual, we invite your comments. A Land use glossary explains some of the terms used in these articles.]

As we build, so shall we live. — Richard Register

As we look for answers to the twin crises of peak oil and climate change, as well as the widespread symptoms of social decay and collapse such as elevated crime, degraded communities, and broken families, urban design and land use must be one of the central ways that we reform our way of life if we hope to survive. Carbon-neutral cities and towns have the potential to heal our broken culture and create a more desirable, more comfortable, more creative, more healthy, and less stressful civilization. By rethinking and redeveloping our cities, towns, and villages, we can put more people back in touch with the land while freeing them from the shackles of car culture.

Ecocity Principles

The ecocity concept is changing the dialog between the social justice and environmental movements; one ideal must not necessarily be sacrificed for the other. The ecocity movement offers many tools and formulations which can serve to drastically reduce our physical footprint on the earth and thus our carbon footprint. In both the rural setting and the urban, these concepts can be used to create a more fulfilling life for people of all means and backgrounds and greater flexibility in terms of lifestyle choices, residential choices, occupational choices, and transportation choices. Three key principles underlie this shift.

Principle 1: Reversal of the transportation infrastructure hierarchy

cars--->transit--->bikes--->pedestrians

pedestrians--->bikes--->transit--->cars

In order to fully take responsibility for energy security, we must look at one of our major uses of energy: transportation. Private automobiles are the primary means of transportation and by far the most inefficient. By creating conditions in our built environment favorable to walking, biking, and public transportation and by restricting access to private autos, we can take back our public space and reduce our energy consumption significantly.

Auto restrictions have successfully transformed many cities into healthier and wealthier communities. Limited auto access neighborhoods use barriers, parking restrictions, traffic calming, and slow streets to reduce car travel. Narrower streets save money and resources used in their upkeep, are safer by slowing traffic, use less land that could be used as public space or for growing food, reduce runoff, hold less heat and thereby reduce air conditioning, and allow for a greater sense of community ownership. An initiative to reduce paving and parking can facilitate this transition, and tradable depaving credits for private businesses and residents are a useful tool to further this change.

A citywide 20mph speed limit both saves fuel and creates safer conditions for pedestrians and bicyclists. Pedestrian areas can demarcate neighborhood centers and can be used as a tool to strengthen the local economy. This will become necessary for continued access to essential goods and services as the failed big box-model of business breaks down. Car-free housing can save residents money and further reduce the total number of cars in the city, also reducing the need for on-street parking. As fuel prices rise, Ithaca residents will continue to seek formal and informal car-sharing arrangements. Minibuses, delivery vehicles, car co-ops, and electric cars and trucks allow flexibility in moving materials and in the transportation of elders and car-free residents. Tax breaks for car-free living and car sharing make economic sense, especially if the city is able to receive carbon credits for these practices.

As much as we reduce car use, we need to increase access to other ways of getting around. Non-motorized modes such as walking, biking, skating, pedicabs, and cargo bikes should get the priority. Where bike facilities are improved, ridership increases greatly, so every effort should be made to allow access to both urban and rural residents to these facilities. Next comes fixed rail transit powered by renewable energy; personal rapid transit, trolleys, light rail, and traditional heavy rail are all forms that this change could take.

Every effort should be made to restrict the use of private cars in the city. More ways to reduce downtown auto traffic include car/van pools and park-and-riders, which should receive credits from the city. Public transit is subsidized enough to make it more affordable than private cars. Idealy, cars would be taxed if they choose to enter the city center.

Principle 2: Increasing density in walkable centers linked by transit

As the emphasis of our city moves away from car culture, the opportunity arises to change the face of our neighborhoods for the better. The first step is to identify neighborhood and municipal centers that will serve as the nuclei for redevelopment. We can then create specific area plans via a consensus-based planning process. Most medium density areas can be preserved while increasing population in the two to three blocks around centers. Centers themselves can be much denser and more diverse than current neighborhood centers. Clustered businesses and services would line the streets, and essential services would also be easily accessible at street level. Dwelling clusters on the upper floors would put many more people within the new center itself. The public spaces of the center, including the street, would create a maximum of usable, flexible space for neighborhood residents. These neighborhood enhancements demonstrate access by proximity; being there versus getting there.

Car-Free State Street. (Drawing by Rob Morache.) A car-free corridor would create a

backbone of pedestrian and bycicle connections through the center

of the city, melding the West End and Commons into a unified whole.

Notice the overhead rail of the PRT (personal rapid transit)

system, one possible form that a fixed transit network could take.

Infill development in current parking lots as well as added

stories would work together to create a much more densly populated

downtown within easy walking, biking, and transit distance from

anywhere in the city, filling the current need for more affordable

housing downtown.

All of these developments would be centered around a transit stop, which would connect the neighborhood with the rest of the city without the need for automobiles. This type of nodal development can only be effective when linked by fixed transit lines. Transit would run throughout the city and connect rural areas along major transit corridors. Although questions exist about how to pay for such a transportation system, we should consider how much we spend collectively on private automobiles, auto infrastructure, repairing the damage done to our bodies and our communities by an auto-centric culture — not to mention oil wars, accounting for cross-cultural costs that can only be estimated.

These improvements can be created mostly by infilling where parking lots currently exist and by enhancing public and semi-public spaces such as front lawns, back yards, and alleys. Existing structures can also be remodeled to accommodate one or two extra floors for commercial spaces, apartments, workshops, etc. Spaces between buildings can be infilled to allow even more diversity of smaller spaces for apartments, studios, offices, etc. Rooftop gardens, cafes, and social spaces can use utilize space that is normally inaccessible and create a more three-dimensional usable space. All of this would be constructed to harmonize with the current built environment.

As the city becomes denser, the amount of walking and cycling to work increases, people are able to work much closer to where they live, and transit ridership increases. Along with the reduced reliance on private cars, air quality in the city will be greatly improved and street congestion will decrease. The dense neighborhood centers can be designed to conserve energy, allow easier recycling and waste management, and allow urban agricultural space. Tools such as the city's comprehensive plan, specific area plans, and neighborhood vision statements can all be used to great effect in shifting development into neighborhood centers. Transfer of Development Rights, or TDR, has also been used effectivly to encourage private developers to build where and what residents want. For more on TDR, see www.cascadeagenda.com/tdr.

Principle 3: Urban cooperative blocks, eco-hoods, and village clusters

The last key principle of ecocity and energy descent crosses from the physical sphere into the social. Urban cooperative blocks, or eco-hoods, are the reconfigured neighborhoods of a low-energy future. Some of the main features of the cooperative block are the common house, common yards and gardens, common parking, common cooking and eating areas, and toolshares. Through resource sharing, cooperative neighborhoods are able to reduce energy consumption while maintaining their relative level of comfort, creating and deepening community structures. There are many models for achieving more cooperation and thus energy savings in neighborhoods, including condominium corporations, non-profit groups, mutual housing associations, limited equity cooperatives, community land trusts, and more anarchic and informal cooperative living situations.

Other ways exist to increase cooperation in neighborhoods. One significant way to build community is to take down fences in backyards to free up more area for other uses. Much wasted space that could be used for growing food and community uses is locked away in the back yards of our cities and largely forgotten. By removing these physical barriers, we also remove some of the psychological barriers that prevent neighbors from approaching each other. Traditional urban design elements that focus on the community, including the zocolo or the piazza, can be forged from the newly freed spaces and allow for natural cooperation and togetherness. Vacant and underused lots can also be transformed into community spaces such as playgrounds and gardens. It must be shown that these changes will benefit residents, encouraging them to take part in the transformation. Tax breaks for urban gardens, city monies for new public spaces, and neighborhood-based celebrations are just some of the possible incentives to induce these changes. We must create sites that demonstrate these innovations now so that people can see the advantages and learn to create them in their own back yards.

Here are some other ideas for creating deeper community connections and energy savings:

Eco parks. Parks can be transformed with the addition of multi-use buildings, community gardens, edible landscaping, bike street and transit connections, and natural wastewater treatment and drainage. In addition, underused public and private spaces can be converted to pocket parks. These should be as diverse as the neighborhoods which they inhabit and should include BBQs, playgrounds, smaller community gardens, basketball courts, and other multi-use facilities. Major parks, such as Stewart Park, the City Golf Course, Washington Park, Cascadilla Gorge, etc., could each have their own theme.

Neighborhood consultas. Neighborhood grassroots governance, planning, and education. Facilitation training, consensus planning, charrette-style development planning, classes and internships for teens and low-income residents, eco-hood programs.

Intersection repairs. Piazzas can be created to calm traffic and create community space. Using natural building and public art, intersections become community spaces that knit together the physical space of a neighborhood. Each neighborhood designs and builds its own piazzas.

Green clubs. Building community and greening the neighborhood; stream stewards, tree-lawn gardeners, community garden co-ops, sew green, mutual aid networks, green workers co-ops, bike clubs, food preservation groups, social clubs, reading and learning circles.

Greenstreets and bikestreets. A network of pedestrian-only greenstreets can take advantage of underused inter-block areas. The greenstreets should connect neighborhood commercial centers, ecoparks, pocket parks, and community gardens. Bikestreets can network between all neighborhoods and parks, providing a sustainable and easy transit mode within reach of all residents. Bikeways should spread out in all directions from the city. All transit connections should have bicycle lockups, bike racks, and special service for bikers to surrounding towns. Example: Cascadilla greenway.

Neighborhood CSAs. To produce a maximum amount of food, open areas should be managed by a neighborhood CSA: a loose coalition of gardeners, urban farmers, and youth program participants. Fruit and nut trees, berry-producing shrubs and canes, and other produce can be planted on every block, in every tree lawn, and in all parks. Connections can also be made with land outside of town that is within walking distance of bus routes and bikeways. Modest housing facilities can enable part-time land access to a wide spectrum of neighborhood residents. Some examples of the neighborhood CSA would be a neighborhood farm at the Ithaca Community Gardens and a neighborhood orchard at the Ithaca Farmer's Market.

Coming next: The Country.

Land use glossary

Land use bibliography

Land use resources